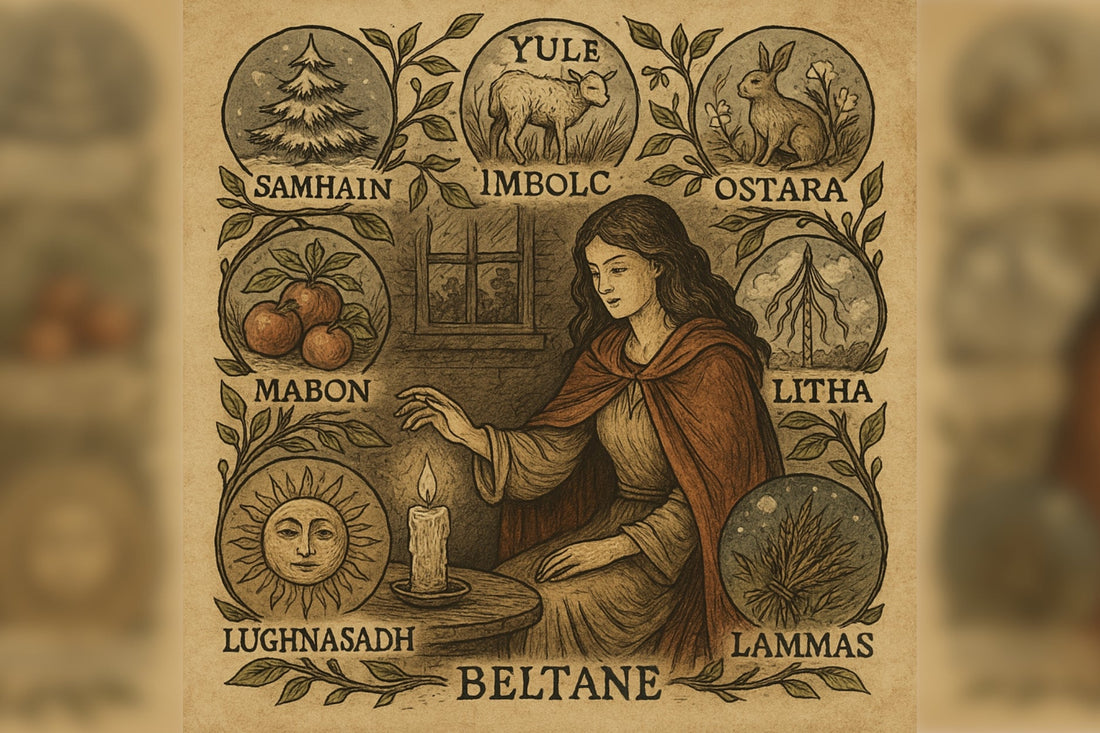

What Are The Eight Sabbats in Wicca?

Share

If you've ever tried to learn the names of the eight sabbats in Wicca, you might’ve felt like you were cramming for a test on ancient festivals you’d never heard of. Just like the Wiccan Rede, people mix them up all the time. Some forget a few. Others recite them like a chant without knowing what they mean. And to be fair, it’s not exactly obvious. The names come from a mix of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and modern Pagan sources. Some sound like they’re pulled from a history textbook, others from a fantasy novel.

These eight festivals form what's called the “Wheel of the Year” – a cycle that maps nature’s turning points across the seasons. They’re split between four solar sabbats (solstices and equinoxes) and four cross-quarter days that fall in between. Some Wiccans call the cross-quarter sabbats the “greater” ones, but not everyone agrees on that. In fact, not everyone celebrates all eight. Wicca isn’t like Catholicism – there’s no pope, no Vatican, no official rulebook.

The Wheel of the Year is less about dogma and more about rhythm. It's used to mark the growth, death, and rebirth seen in both nature and ourselves. Some see it as a mystical calendar; others treat it more like a symbolic reminder to pause, reflect, and realign. Either way, each sabbat has a history, a mood, and a meaning. So if you're wondering what exactly Lughnasadh is, or why Wiccans get excited about the equinox, you're in the right place. Let’s break down the eight sabbats and what they actually stand for.

Key Points:

- The eight Wiccan sabbats follow the natural cycle of the year, marking both solar events (solstices and equinoxes) and seasonal turning points (cross-quarter days).

- Each sabbat has distinct themes - like renewal at Imbolc, abundance at Litha, and remembrance at Samhain - that reflect both the outer world and inner life.

- Wiccan sabbats aren’t fixed rituals; they’re flexible frameworks that practitioners adapt based on their region, lifestyle, or personal path.

- Together, the sabbats form a continuous cycle that helps people reconnect with nature, mark time meaningfully, and stay grounded in seasonal change.

The Wheel of the Year Explained

At the centre of Wiccan seasonal practice is the Wheel of the Year: a repeating cycle of eight sabbats spaced roughly six to seven weeks apart. It’s not just a calendar - it’s a symbolic map of nature’s rhythms. Four of the sabbats fall on solar events: the solstices and equinoxes, when the position of the sun marks the longest, shortest, or equal-length days of the year. These are Yule (winter solstice), Ostara (spring equinox), Litha (summer solstice), and Mabon (autumn equinox).

The other four sabbats - Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh, and Samhain - are known as cross-quarter days. They fall between the solar festivals and often mark agricultural or pastoral milestones, like the start of lambing season or the first grain harvest. Some Wiccans consider these the “greater” sabbats because they’re rooted in older folk festivals and often feel more emotionally charged.

Not all Wiccans observe every sabbat. Some lean more heavily into the ones that match their regional seasons. For example, Samhain might feel completely out of place in the Southern Hemisphere if celebrated in late October, since that’s springtime there. Many southern practitioners flip the calendar six months to match their natural cycle - so Yule is in June, Beltane in November, and so on.

It’s also common for people to adapt the sabbats based on their own spiritual leanings. Some follow them as literal seasonal markers; others see them as metaphors for growth, change, and personal cycles. That’s the thing about the Wheel: it turns for everyone, but how you walk it is up to you.

Photo by Pixabay: https://www.pexels.com/photo/brown-pinecone-219778/

Yule (Winter Solstice) – Return of the Sun

Yule marks the longest night of the year, falling around 21 December in the Northern Hemisphere. It’s the winter solstice - the point when the sun is at its lowest, and daylight begins to slowly return. For Wiccans, it symbolises rebirth. The God, who died at Samhain, is born anew as the sun-child, bringing with him the promise of warmth and light.

A lot of Yule’s traditions will feel familiar. Decorating evergreens, burning a Yule log, exchanging gifts, lighting candles - all of these were part of pre-Christian European solstice celebrations long before they were absorbed into modern Christmas customs. But where Christmas focuses on a single holy birth, Yule is more about the turning of the tide. It’s a cosmic reset button.

Some Wiccans hold ritual circles at sunset or sunrise to welcome the returning light. Others keep things simple: lighting a single candle in the dark and sitting with the silence. Personally, I find Yule to be the most calming of all the sabbats. There’s no pressure to be productive or outwardly joyful. It’s a still point in the year, a moment to rest, reflect, and gather strength.

While the world outside might feel cold and lifeless, Yule reminds us that the cycle hasn’t ended - just paused. The return of the sun, even if barely noticeable at first, is a quiet promise that things will grow again.

Imbolc – First Stirring of Spring

Imbolc arrives around 1 February and catches people off guard. It’s not warm. The trees are still bare. But something has shifted. The days are getting slightly longer, lambs are being born, and the first shoots of green begin to push through the frost. It’s a quiet sabbat, but a powerful one.

The word “Imbolc” is often said to come from an old Irish term meaning “in the belly,” referring to pregnant ewes. It’s associated with Brigid, the Celtic goddess of hearth, healing, poetry and fertility. Many Wiccans honour her at this time, lighting candles or crafting Brigid’s crosses from straw. In some traditions, Imbolc is also a time for cleansing, both physical and spiritual - sweeping out stale energy to make space for what’s next.

There’s something understated about this sabbat that I really like. It’s not loud or showy. It’s that flicker of determination that returns after winter’s fog. Some Wiccans use the day for rededications or initiations, since it marks the very beginning of the growing season - not the full bloom, but the first pulse of life returning.

You don’t need fields or lambs to mark Imbolc. Light a few white candles. Open the windows, even for a moment. Clean out a cupboard or delete the apps you never use. Anything that clears space or invites renewal fits the spirit of this sabbat. It’s the first breath after stillness.

Ostara (Spring Equinox) – Balance and New Beginnings

Ostara falls around 20 or 21 March, when day and night are almost exactly equal. It marks the spring equinox, the moment when light overtakes dark and everything begins to wake up properly. In Wiccan practice, this sabbat is all about balance, growth, and potential.

The name “Ostara” comes from Jacob Grimm’s reconstruction of a supposed Germanic goddess, related to the Anglo-Saxon Ēostre. There’s not much historical evidence for her, but the associations stuck: eggs, hares, flowers, and the rising sun. Modern Easter inherited plenty of these symbols, just stripped of their original seasonal meaning.

For Wiccans, Ostara is a turning point. The earth is alive again. Seeds go into the ground. Ideas begin to take shape. Rituals often focus on planting - literally or metaphorically. Some people start herb gardens. Others write intentions on paper and bury them in the soil. It’s also a good time to reflect on inner balance: between work and rest, solitude and connection, giving and receiving.

I didn’t connect with Ostara at first. It felt too pastel, too much like a watered-down Easter. But when I started actually paying attention to what was happening outside - buds forming, birds nesting, light staying longer each evening - it clicked. There’s a quiet magic in everything beginning again, especially if you’ve just crawled out of a tough winter. Ostara reminds us that balance isn’t static - it’s movement, a point between two tipping forces.

Beltane – Fire and Fertility

Beltane lands on 1 May and hits like a burst of energy. Where Ostara is all about potential, Beltane is about full-blown life. It’s the sabbat of fire, fertility, passion, and growth. In older Gaelic traditions, Beltane marked the start of the light half of the year - a time for driving cattle to summer pastures, lighting bonfires, and blessing the land.

Wiccans often celebrate it as the symbolic union of the God and Goddess, a sacred joining of masculine and feminine forces that fuels the abundance of summer. That might sound overly poetic, but the core idea is straightforward: things are growing, blooming, and coming alive. Maypole dances, flower crowns, and jumping over fires are just some of the ways people mark the day.

Beltane rituals are usually held outdoors. They’re loud, earthy, and often filled with laughter. If Samhain is the Wiccan New Year, then Beltane is the wedding party - chaotic, joyful, and fully in the moment. There’s an openness to sensuality and celebration that you don’t always see in other parts of the year.

For me, Beltane is about movement. It’s the point where plans stop being abstract and start to take shape. It’s also about connection - with nature, with other people, with your body. Even if you’re not dancing around a maypole, just sitting in the sun with bare feet on the grass can feel like a ritual in itself.

![]()

Photo by Bob Jenkin from Pexels: https://www.pexels.com/photo/iconic-stonehenge-under-a-blue-sky-32419261/

Litha (Summer Solstice) – Peak of Light

Litha falls around 21 June, marking the summer solstice - the longest day and shortest night of the year. The sun is at its height, the earth is full, and everything feels expansive. In Wiccan belief, this is when the God is at the peak of his power, before he begins to slowly decline as the days grow shorter.

Unlike Beltane’s raw energy or Imbolc’s quiet stirrings, Litha is about standing still in the brightness. It’s a moment to acknowledge fullness before the turning begins. Rituals often take place at dawn or dusk, sometimes around bonfires, to honour the sun’s power and the natural world in full bloom.

There’s also a layer of duality here. As much as Litha celebrates abundance, it also marks the start of the sun’s descent. From this point forward, the light will begin to lessen. Some Wiccans use this sabbat to reflect on what has grown in their lives so far that year - and what needs to be released before the next cycle begins.

For me, Litha has a calm, glowing mood to it. There’s pressure to make the most of the light, but also an invitation to simply enjoy it. It’s a time to slow down, notice the details, and take pleasure in things that are fully alive. Whether that means walking barefoot through grass, picking herbs, or just lying in the sun for a while, Litha encourages presence over productivity.

Lughnasadh / Lammas – First Harvest

Lughnasadh, also called Lammas, is celebrated around 1 August and marks the first of the three harvest sabbats. While the names differ - Lughnasadh has Celtic roots linked to the god Lugh, and Lammas comes from the Old English for “loaf mass” - the theme is the same: gratitude for the early grain harvest and the effort it took to get there.

This sabbat is about work paying off. The seeds planted in spring have grown into something real, something tangible. Traditionally, the first loaf of bread made from that year’s wheat would be offered in thanks. In modern practice, Wiccans might bake bread, gather wild herbs, or make offerings of food to honour the land and their own progress.

It’s a time of reflection, but not the quiet kind. Lughnasadh has a rugged, earthy feel. It celebrates sweat, skill, and the value of labour. For those in rural communities, it still carries a very real connection to the land. For those of us in cities, it’s a chance to stop and acknowledge whatever “harvest” we’ve brought in - creative, emotional, financial, or otherwise.

Personally, I enjoy Lughnasadh for its groundedness. There's no pretense. It’s about effort and reward, about honouring the work you’ve done and starting to prepare for what’s coming next. It reminds me that growth isn’t always glamorous, but it’s always worth marking.

Mabon (Autumn Equinox) – Second Harvest

Mabon arrives around 21 September, when day and night stand in balance once again. It’s the autumn equinox - the second of the solar sabbats - and marks the middle of the harvest season. If Lughnasadh celebrates the first fruits, Mabon is the time to gather the rest, to take stock of what’s left, and to begin slowing down.

The name “Mabon” is relatively modern. It was popularised in the 1970s and refers to a character from Welsh mythology. Older names for this sabbat include Harvest Home or the Feast of the Ingathering, which feel more directly connected to its agricultural roots. Some Wiccans embrace the newer term; others avoid it in favour of more traditional or descriptive names.

Rituals at Mabon often focus on gratitude. Altars might be decorated with apples, gourds, grapes, and autumn leaves. Some people use the day to share food with friends or family, echoing the communal spirit of a harvest festival. Others treat it as a moment of personal reflection - what have I achieved this year? What do I still need to finish? What am I ready to let go of?

Mabon is my reset button. It doesn’t carry the emotional intensity of Samhain or the brightness of Litha. Instead, it has a mellow, measured feeling. A kind of emotional tidying-up. It’s the part of the year where I pause, breathe, and start putting things in order for the descent into winter. It’s not just about giving thanks - it’s about making peace with what’s done and starting to accept what isn’t.

Samhain – Festival of the Dead and Wiccan New Year

Samhain (pronounced sow-in) falls on 31 October, though many Wiccans extend the celebration over several days. It marks the final harvest, the descent into winter, and the end of the Wiccan year. It’s the sabbat most closely tied to death - but not in a morbid way. It’s about endings, ancestors, memory, and release. It’s also the root of what we now call Halloween - so you can blame that on Samhain!

In Wiccan tradition, Samhain is when the veil between the worlds is thinnest. Spirits can be more easily contacted or honoured. Many practitioners light candles for those who’ve passed, leave offerings at altars, or hold silent meals with a place set for the dead. It’s not just about grief - it’s about connection. For some, this is the most sacred sabbat of all.

Samhain is also a time of personal reckoning. What needs to end? What no longer serves you? What are you willing to let go of before the long dark settles in? These questions don’t always have easy answers. But facing them is part of the point. Just as the earth rests in winter, so too should we.

I’ve always found Samhain incredibly grounding. It’s not about costumes or horror films - though there’s room for fun too - it’s about facing the truth that everything changes. Everything dies. But nothing is lost forever. Memory, legacy, and spirit endure. That’s what Samhain honours. It’s the close of the year’s story, but also the quiet start of the next.

Why the Sabbats Matter Today

In a religion with no fixed dogma, the eight sabbats offer something rare: structure without rigidity. They give Wiccans a way to mark time that doesn’t rely on human-made calendars, school terms, or corporate holidays. Instead, they follow the land. Light, dark, growth, decay. The cycle keeps turning, and the sabbats help people move with it rather than against it.

Not every Wiccan celebrates all eight. Some focus only on the four greater sabbats. Others blend the Wheel of the Year with older folk traditions, local customs, or their own intuitive practices. In the Southern Hemisphere, the whole calendar is flipped - Yule in June, Samhain in May - because the wheel has to match the actual seasons to make any sense. There's no one right way to do it.

In cities, where most people no longer harvest anything except Deliveroo, the sabbats still offer relevance. They’re markers for checking in. What’s growing in your life? What needs pruning? What have you finished? Where are you heading next? Whether you’re lighting candles at your kitchen table or standing in a field with twenty others, the sabbats give shape to your year - and to your inner world.

They also matter because they slow you down. In a culture obsessed with speed, productivity, and outcome, the sabbats ask you to pause. To notice. To remember that time isn’t just hours and deadlines - it’s seasons, shifts, cycles. That’s what makes them powerful. Not the rituals themselves, but what they anchor you to.

Summary

The eight sabbats of Wicca form more than just a calendar - they trace a cycle that mirrors nature’s rise and fall. From the quiet promise of Imbolc to the full blaze of Litha, and from the first golden grains of Lughnasadh to the deep stillness of Yule, each sabbat marks a shift in the natural world and offers a chance to reflect on your place within it.

They’re not commandments, and no one’s keeping score. Some Wiccans celebrate all eight, while others don’t. Some hold full rituals with circles and chants; others light a single candle and call it enough. That flexibility is the point. The Wheel isn’t rigid, it turns at its own pace, and so can you.

What matters is the rhythm. Noticing the shift from light to dark. Taking time to honour growth, harvest, rest, and return. In a world that rarely stops moving, the sabbats create pockets of meaning - reminders that time is not a straight line, but a loop. Always turning. Always beginning again.

So whether you’re walking in the woods at Samhain, baking bread at Lughnasadh, or simply watching the sunrise at Ostara, you’re moving with something ancient. And that, even now, still matters.

2 comments

I am doing some research for a book and this blog was really beautifully written and really concise. I am really glad I happened upon this. I feel like not only was it super knowledgeable but it also reminded me that it is important to slow down, be grateful and be aware of your surroundings. Thank you for the knowledge :)

Just wanted to tell you this is one of the best blogs on the wheel of the year I’ve read. concise, accurate and offers lots of ways for people to connect to the different sabbats. Thank you :)