What is the Satanic Temple?

Share

The Satanic Temple (from hereon referred to as TST) isn’t what most people imagine when they hear the word “Satanic.” Despite the ominous name, this group doesn’t worship demons or conduct secret rituals. Instead, it’s a legally recognised non-theistic organisation that uses the symbol of Satan as a figure of rebellion and reason. Founded in 2013, TST is better known for its courtroom battles and public protests than for anything truly occult.

In recent years, the group has grabbed headlines for its provocative activism, particularly in the fight for religious freedom, reproductive rights, and the separation of church and state. From challenging government-sponsored religious displays to launching "After School Satan Clubs," they use their platform to hold authorities accountable when religious privilege threatens public neutrality.

For some, their approach is clever and necessary. For others, it’s confrontational and uncomfortable. But at the heart of the controversy is a simple idea: if one religion gets special treatment, others - including TST - must be granted the same or none at all.

History and Founding

The Satanic Temple was founded in 2013 by Lucien Greaves and Malcolm Jarry as an effort to blend activism, satire, and legal advocacy. What started as a small-scale performance art project aimed at challenging religious hypocrisy quickly transformed into a formal organisation with a growing following.

Greaves, often the public face of TST, has been clear from the beginning: the group’s goal isn’t to spread chaos or convert people. Instead, they use Satan as a symbol of resistance - drawing inspiration from literary works like Paradise Lost by John Milton, where Satan represents defiance against unjust authority.

The early years of the Satanic Temple saw rapid growth in public interest, largely due to their creative and bold campaigns. What began as an artistic and intellectual protest became a well-oiled organisation advocating for religious equality through legal channels.

Today, the Satanic Temple operates internationally, with numerous chapters across the United States, the UK, and beyond. Their aim remains consistent: to challenge the misuse of religion in government and defend personal liberties for everyone - religious or otherwise.

Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Core Beliefs and Principles

At its core, the Satanic Temple isn’t a religious organisation in the traditional sense. Its members don’t believe in a literal Satan or any supernatural being. Instead, they embrace secularism and use Satan as a metaphor for questioning authority, promoting individual autonomy, and standing against unjust power structures.

The group's philosophy is built around seven fundamental tenets, which outline their moral framework:

- Compassion and empathy: Act with kindness towards others, reflecting a commitment to fairness and understanding.

- Justice and fairness: Stand for justice, even when it’s difficult or unpopular.

- Bodily autonomy: Every person has control over their own body, free from outside interference.

- Respect for the freedoms of others: The freedom of one person shouldn’t infringe on the freedom of another.

- Belief should align with scientific understanding: Beliefs must evolve with new evidence rather than staying rigid.

- Mistakes are opportunities for growth: Admit when you're wrong and seek to improve.

- Compassion and wisdom over dogma: Be guided by reason and empathy, not blind adherence to rules.

These tenets shape the Temple’s activism and legal arguments. For example, their stance on reproductive rights is grounded in bodily autonomy - the belief that individuals should have control over their own medical decisions. Unlike many religious organisations, TST doesn’t claim moral superiority. Instead, it presents these tenets as a flexible framework for ethical living based on evidence and reason.

Symbolically, Satan represents the eternal questioner - the figure who challenges oppressive rules rather than submitting to them. This non-theistic approach sets the Satanic Temple apart from religious traditions that rely on faith in the supernatural.

The group also differs from typical "atheist" organisations. While many secular groups focus purely on advocacy for science or reason, TST blends those elements with powerful visual and symbolic protest. By leaning into the “Satanic” aesthetic, they highlight double standards in how society treats different belief systems.

For members, the point isn’t to shock for the sake of it - it’s to remind people that freedom of belief must apply equally, regardless of how uncomfortable some ideas may seem.

Photo by Mike Von on Unsplash

Activism and Campaigns

The Satanic Temple is best known for its activism, using legal challenges and public demonstrations to highlight issues of religious privilege and individual rights. Their campaigns often spark controversy but force conversations about fairness, public space, and constitutional freedoms.

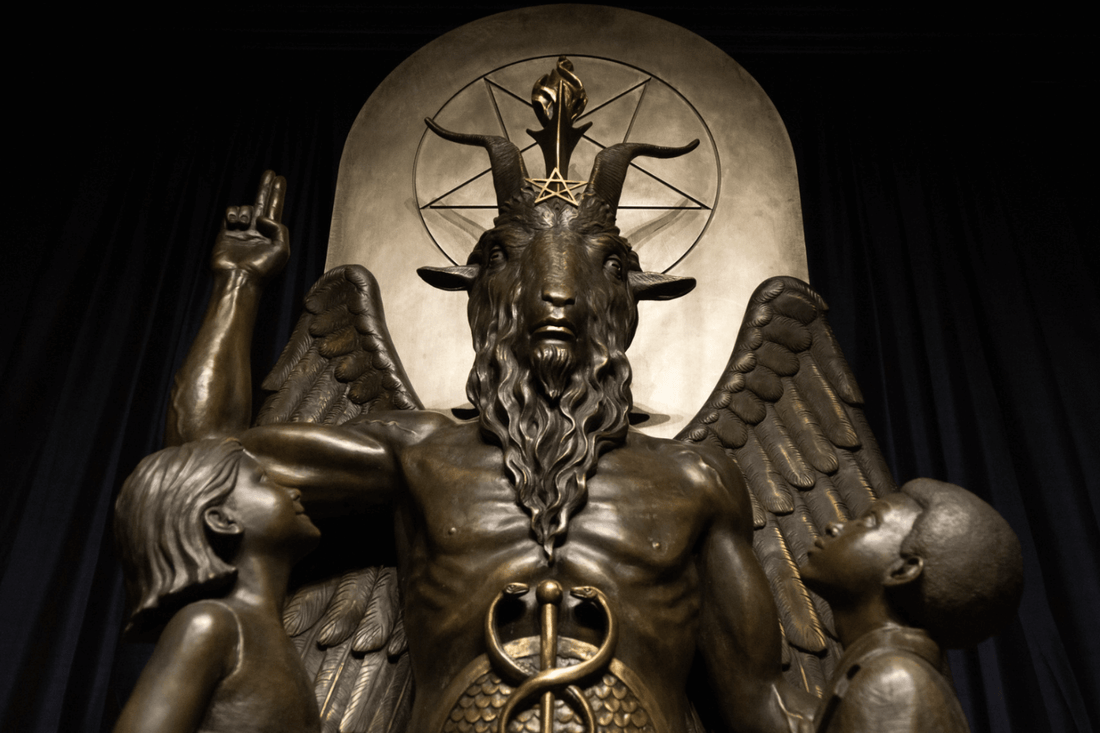

One of their most notable efforts came in 2015, when they unveiled the Baphomet statue - a 2.7-metre bronze figure seated on a throne surrounded by two children looking up in admiration. This wasn’t just for spectacle. The statue was meant to counter a Ten Commandments monument at the Oklahoma State Capitol. Their argument was clear: if Christian symbols are allowed on government grounds, symbols representing other belief systems must also be permitted, or none should be displayed at all. Oklahoma eventually removed the Ten Commandments monument altogether.

In the area of education, the Satanic Temple launched "After School Satan Clubs" in response to Christian evangelical groups hosting after-school Bible programmes in public schools. These clubs focus on teaching critical thinking, science, and empathy rather than any form of religious doctrine. The idea isn’t to recruit children to Satanism but to provide a secular alternative that respects the separation of church and state.

TST’s activism also extends to reproductive rights. In states with strict abortion laws, they’ve filed lawsuits arguing that such restrictions violate their members' religious rights under the principle of bodily autonomy. For TST members, access to abortion and reproductive care can be viewed as a religiously protected practice - turning the religious freedom argument often used by anti-abortion groups on its head.

Their campaigns also include public actions, such as "Pink Masses" (ceremonies intended to symbolically ‘queer’ the marriages of deceased anti-LGBTQ figures - quite funny really!) and protests against the use of public funds to support religious initiatives. These acts are deliberately provocative but grounded in legal reasoning, using public spectacle to force institutions to justify religious privilege in law and public policy.

Critics often argue that the group’s tactics are inflammatory. Supporters, however, view them as necessary in a climate where religious influence frequently shapes laws and public spaces. By forcing authorities to confront uncomfortable questions, the Satanic Temple has successfully shifted debates about religion and secularism into mainstream public discourse.

Public Perception and Criticism

The Satanic Temple’s approach divides opinion. Supporters see them as defenders of civil liberties, using wit and legal expertise to expose inconsistencies in how religion is treated in public life. Detractors often dismiss them as provocateurs looking to stir outrage for attention.

One common criticism is that TST is deliberately antagonistic towards Christianity. Many religious groups view their use of Satanic imagery as needlessly inflammatory, arguing that it mocks faith rather than promoting equality. TST leaders, however, counter that their work only appears antagonistic because certain religious groups expect preferential treatment. Their position is simple: if governments uphold religious neutrality, there’s no conflict.

Some critics argue that the group’s stunts, like the Baphomet statue and After School Satan Clubs, are publicity grabs rather than meaningful activism. However, TST members point out that nearly every campaign is backed by legal filings and a consistent defence of constitutional rights. For instance, their lawsuit against Missouri’s abortion restrictions wasn’t just a headline - it pushed the argument that religious freedom laws should apply to all beliefs, not just Christian ones.

Internally, there has also been occasional friction. Some early members parted ways, criticising the organisation for becoming too hierarchical or for focusing too much on lawsuits rather than community-building. TST’s leadership has responded by highlighting their role as a national advocacy group rather than a religious community in the traditional sense.

The media’s portrayal of TST has also shifted over time. Early coverage often leaned into shock value - focusing on the imagery of Satanic symbols and dark robes. More recent reporting, however, tends to take their political and legal arguments seriously, especially as their lawsuits over abortion rights and church-state separation have become more relevant. Documentaries, such as Hail Satan?, have provided a more nuanced view, portraying the group as thoughtful and strategic rather than gimmicky.

Despite the criticism, TST has grown substantially, with thousands of registered members worldwide. The group’s ability to provoke debate - and to back up their rhetoric with court filings - has made them a fixture in discussions about religious freedom and state overreach. Whether seen as defenders of justice or as professional agitators, they have undeniably shifted the conversation around what religious freedom really means in modern society.

TST vs. Church of Satan

Although they are often lumped together, the Satanic Temple (TST) and the Church of Satan (CoS) are fundamentally different organisations with distinct goals. The Church of Satan was founded in 1966 by Anton LaVey and is rooted in individualism, self-empowerment, and atheistic ritualism. Its central text, The Satanic Bible, outlines a philosophy that rejects external moral codes and celebrates personal ambition.

In contrast, the Satanic Temple was founded decades later with a focus on activism, legal reform, and public engagement. While both groups use Satanic imagery, their interpretations diverge sharply. For LaVeyans, Satan represents the strength of the individual and a rejection of religious dogma. For TST, Satan is a symbol of rebellion against tyranny and a champion of justice and free thought.

Another key distinction is their approach to public life. The Church of Satan typically avoids political activism and views religion as a private, individual experience. Members often critique TST’s legal challenges and public protests as unnecessary theatrics. In contrast, TST views their activism as essential, arguing that staying silent in the face of religious overreach allows inequality to persist.

While CoS emphasises individualism to the point of rejecting group action altogether, TST functions more like a social justice organisation. They organise collective efforts, such as court cases and public events, to push back against religious privilege and protect civil rights.

The two organisations have even clashed publicly. Church of Satan representatives have criticised TST for using the term "Satanism" to describe what they see as a political movement rather than a true philosophy of Satanic individualism. TST, for its part, dismisses these critiques as outdated and irrelevant, arguing that modern Satanism can - and should - evolve to address contemporary social and political issues.

Ultimately, the difference lies in focus. The Church of Satan centres on personal empowerment and philosophical self-determination. The Satanic Temple prioritises collective action, social reform, and holding authorities accountable for religious bias. Both challenge mainstream religious norms, but they do so in profoundly different ways.

What impact has the TST really had?

The Satanic Temple has become a cultural touchpoint in discussions about religious freedom, civil rights, and the role of religion in public spaces. Their blend of legal activism, symbolism, and performance art has earned them a significant following - and plenty of detractors.

One of the most notable examples of their cultural impact is the 2019 documentary Hail Satan?, which provided a behind-the-scenes look at the group’s early years and key campaigns. The film portrayed TST as an organised and principled movement rather than a provocative sideshow. It helped shift public perception, particularly among younger audiences, who saw TST's actions as a fresh approach to challenging entrenched power dynamics.

Pop culture has also embraced TST’s imagery and philosophy. References to their activism have appeared in television, music, and social media, often as a symbol of defiance against authoritarianism. Their use of humour and bold imagery resonates in an era where memes and visual statements drive online discourse.

Beyond media representation, TST has had a tangible effect on public policy debates. Their legal battles have influenced conversations about what "religious freedom" really means. By highlighting inconsistencies - such as allowing Christian prayers in schools but rejecting secular after-school clubs - they’ve forced legal institutions to confront the double standards baked into many religious privilege arguments.

They’ve also become a symbol for broader movements advocating for reproductive rights. By framing their opposition to abortion restrictions as a religious freedom issue, they’ve introduced a novel argument that challenges conservative legal strategies on their own terms. This approach has resonated with reproductive rights advocates looking for new ways to challenge restrictive laws.

However, their impact isn’t limited to legal wins and media attention. The broader cultural conversation about pluralism and public spaces has shifted due to TST’s work. Issues like the placement of religious monuments on government property - once treated as niche concerns - are now part of mainstream discussions about fairness and equality.

Critics may dismiss the Satanic Temple as attention-seeking, but their influence is undeniable. By turning legal cases and public spectacles into cultural commentary, they’ve forced both the public and policymakers to rethink assumptions about religion, freedom, and fairness. Love them or hate them, the Satanic Temple’s presence in modern culture shows no sign of fading.