What Was The Satanic Panic?

Share

The Satanic Panic was a moral hysteria that gripped the UK, the US, and other Western countries in the 1980s and 1990s. People believed a hidden network of Satanists was abusing children, committing gruesome rituals, and infiltrating society. These fears weren’t based on solid evidence but spread through media reports, unreliable testimony, and the influence of religious and political groups.

It started with a handful of shocking claims that spiralled into a full-blown crisis. Psychologists, police, and the legal system took the accusations seriously, leading to wrongful convictions and shattered lives. High-profile trials, tabloid stories, and TV specials kept the panic alive, convincing the public that something dark was happening behind closed doors.

By the mid-1990s, experts exposed the flaws in the so-called evidence. Many of the accusations came from suggestive questioning, false memories, and mass hysteria rather than actual crimes. While the panic faded, its impact lasted for decades. Even today, echoes of it appear in modern conspiracy theories and internet-fuelled moral panics.

Origins of the Satanic Panic

The roots of the Satanic Panic can be traced back to a mix of cultural, religious, and psychological factors brewing in the 1970s. A rise in evangelical Christianity brought a renewed focus on the idea of spiritual warfare - good versus evil, God versus Satan. Many religious groups saw social changes, such as the growing popularity of heavy metal music, horror films, and Dungeons & Dragons, as signs that Satanic influences were creeping into mainstream culture.

One of the key catalysts was Michelle Remembers, a 1980 book by psychiatrist Lawrence Pazder and his patient-turned-wife Michelle Smith. It claimed to document Michelle’s "recovered memories" of horrific abuse at the hands of a secret Satanic cult. The book was marketed as a true story, despite a complete lack of evidence. It became a bestseller, shaping public fears and influencing police, therapists, and social workers who started seeing Satanic abuse everywhere.

At the same time, concerns over child safety were growing. Reports of child abuse were finally being taken more seriously, but the heightened awareness also created an environment where false accusations could spread. The idea that a vast underground network of Satanists was preying on children took hold, setting the stage for the legal battles and media frenzy that followed.

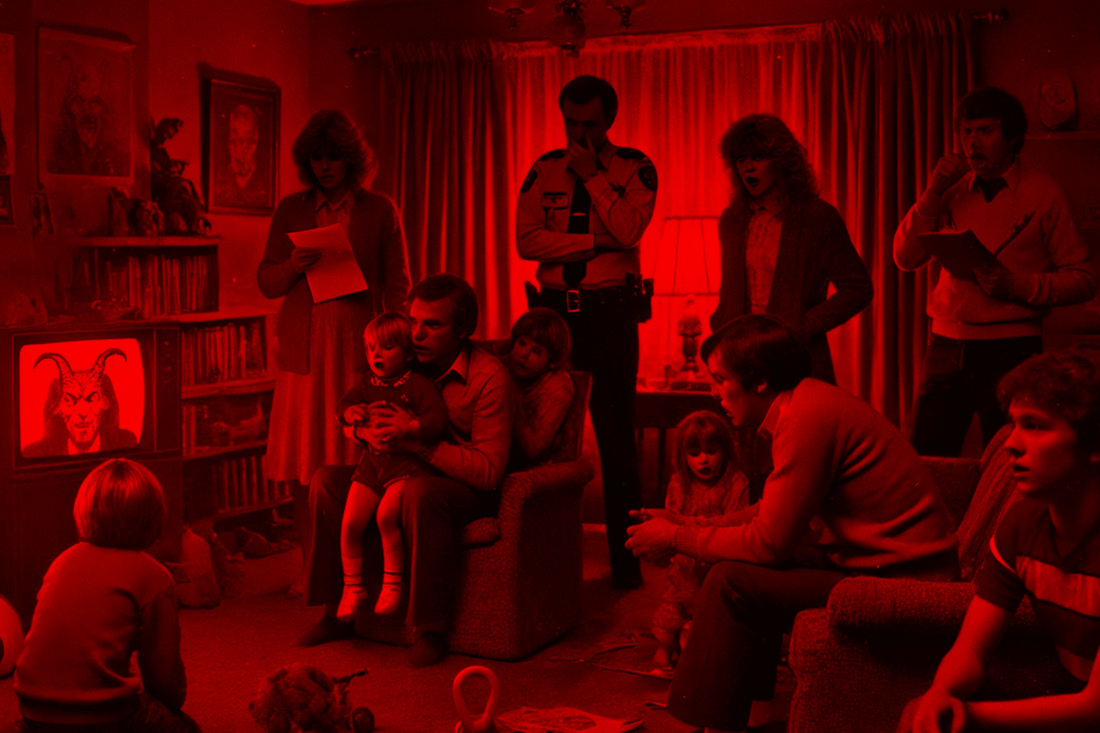

Photo by Jisun Han on Unsplash

The Role of the Media

The media played a massive role in fuelling the Satanic Panic, turning baseless rumours into national crises. Sensationalist news reports, talk shows, and tabloid headlines gave credibility to the idea that Satanic cults were operating in secret, abusing children, and evading justice. Rather than questioning the evidence, journalists and TV producers leaned into the fear, driving public hysteria.

One of the biggest sources of misinformation came from daytime talk shows. Programmes like The Oprah Winfrey Show, Geraldo, and 20/20 aired episodes featuring so-called survivors of Satanic ritual abuse (SRA). These guests told horrific stories of torture, sacrifice, and mind control. Experts, often religious figures or therapists pushing the recovered memory theory, reinforced the claims. The fact that no physical evidence ever surfaced was rarely mentioned.

Tabloid newspapers were just as bad, running front-page stories about Satanic symbols found in schools, mutilated animals in graveyards, and secret underground cults. These reports often relied on anonymous sources or second-hand accounts, with no fact-checking. By the mid-1980s, even respected news outlets were giving airtime to the panic. A 1989 ITV documentary, by The Cook Report, called The Devil’s Work, spread the idea that Satanic groups were targeting children in Britain, despite offering no solid proof.

Fiction also played a part. Horror films about demonic possession and cults, such as The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby, had already primed audiences to believe in dark forces at work. Heavy metal music, with its occult imagery and aggressive lyrics, was accused of corrupting youth. Bands like Iron Maiden, Judas Priest, and Black Sabbath became scapegoats, with religious groups claiming their songs contained hidden messages promoting Satanism.

The constant flood of alarmist stories created a feedback loop. Police and social workers took the accusations more seriously, leading to high-profile trials. Parents panicked, convinced their children were at risk. Lawmakers responded with harsher policies on child protection, often ignoring the lack of credible evidence. By the late 1980s, the idea of Satanic cults running rampant felt like an established fact, even though no legitimate proof had ever been found.

Photo by Strange Happenings from Pexels

The McMartin Preschool Trial and Other High-Profile Cases

The most infamous case of the Satanic Panic was the McMartin Preschool trial, a legal disaster that lasted from 1983 to 1990. What started as a single, unverified accusation turned into one of the longest and most expensive criminal trials in American history, with devastating consequences for the accused.

It began when a mother in Manhattan Beach, California, accused one of the preschool’s teachers, Raymond Buckey, of sexually abusing her son. Despite her history of mental illness and a lack of physical evidence, police sent letters to hundreds of parents, asking if their children had been victims. This sparked mass hysteria, and soon, dozens of children were claiming they had been subjected to bizarre rituals - tunnels under the school, secret rooms, animal sacrifices, and even flights on broomsticks.

The methods used to extract these claims were deeply flawed. Children were subjected to coercive and suggestive questioning by social workers, particularly from the Children’s Institute International (CII). Instead of neutral fact-finding, interviewers encouraged the children to "remember" abuse that had never happened. Some children later recanted, admitting they had been pressured into making up stories to please adults.

Despite the complete lack of evidence, the case went to trial. Over several years, charges were dropped against most of the accused, but the damage had been done. Although no one was ever convicted, the McMartin case reinforced public fears that Satanic cults were targeting children. The accused spent years fighting the allegations, and their reputations were permanently destroyed.

Similar cases followed across the US, Canada, the UK, and Australia. The Kern County child abuse cases in California saw dozens of people imprisoned based on equally dubious testimony. In the UK, the Rochdale and Orkney cases led to children being forcibly removed from their families under accusations of Satanic ritual abuse - accusations that were later discredited.

The common thread in all these cases was the lack of real evidence. No underground cults were ever uncovered. No forensic proof of abuse was found. The supposed tunnels and secret chambers never existed. Yet the legal system, driven by panic rather than facts, allowed innocent people to be accused, jailed, and vilified.

The "Recovered Memory" Controversy

A major driving force behind the Satanic Panic was the rise of "recovered memories" - the idea that traumatic experiences, particularly childhood abuse, could be repressed and later retrieved through therapy. This concept gained traction in the 1980s, despite weak scientific support, and became a key element in accusations of Satanic ritual abuse.

Therapists, often influenced by books like The Courage to Heal (1988), encouraged patients to uncover hidden memories of abuse. Techniques such as hypnosis, guided imagery, and suggestive questioning were used, but rather than retrieving real memories, these methods often created false ones. Patients, genuinely believing they were remembering long-buried trauma, accused family members, teachers, and caregivers of unspeakable crimes.

Many of these accusations led to court cases, tearing families apart. One of the most infamous examples was the case of Paul Ingram, a deeply religious sheriff’s deputy in Washington state. After intense questioning and therapy, he came to believe he had abused his daughters in Satanic rituals - despite initially having no memory of any wrongdoing. Psychologists later determined that his confessions had been coerced, but he was still convicted and spent years in prison.

By the 1990s, the reliability of recovered memories was widely questioned. Cognitive psychologists, including Elizabeth Loftus, demonstrated how false memories could be implanted through suggestion. Studies showed that people could be led to "remember" events that never happened, particularly when subjected to leading questions. This challenged the foundation of many Satanic ritual abuse cases, where convictions relied heavily on unverified testimony rather than physical evidence.

The backlash against the recovered memory movement grew, with lawsuits against therapists who had encouraged false accusations. Some victims of these methods later retracted their claims, realising they had been manipulated. Despite this, the damage had already been done - lives were ruined, innocent people were jailed, and the fear of hidden Satanic cults lingered in the public consciousness for years.

The Legal and Social Consequences

The Satanic Panic didn’t just ruin individual lives - it exposed serious flaws in the legal system, mental health practices, and child protection policies. Overzealous prosecutions, unreliable testimony, and mass hysteria led to wrongful convictions, destroyed families, and a widespread loss of trust in institutions that were supposed to protect people.

One of the most shocking consequences was the number of innocent people sent to prison based on weak or non-existent evidence. In the US, dozens were convicted on charges of Satanic ritual abuse, often serving lengthy sentences before their cases were overturned. Among them was Dan and Fran Keller, a Texas couple who ran a daycare and were sentenced to 48 years in prison in 1992. Their conviction was based on children's testimonies of secret tunnels, baby sacrifices, and flying through the air - none of which had any physical proof. After spending 21 years behind bars, they were released in 2013 when their case was deemed a miscarriage of justice.

In the UK, similar accusations led to the wrongful removal of children from their families. In the Rochdale case (1990), social workers took at least 20 children from their homes, claiming they were victims of Satanic abuse. The same happened in the Orkney case (1991), where nine children were seized by authorities in Scotland. In both cases, no evidence of abuse was ever found, and the children were eventually returned - but only after suffering significant emotional trauma.

Law enforcement agencies played a key role in escalating the panic. Police forces across the US and UK produced training manuals warning officers about supposed Satanic symbols, ritualistic crime scenes, and hidden cult activity. These documents, often written with input from religious fundamentalists rather than criminologists, encouraged police to treat even ordinary crimes as potential signs of a vast underground conspiracy.

The panic also reshaped how child abuse cases were handled. While the growing awareness of child protection was necessary, the Satanic Panic led to an overcorrection. Social workers, afraid of missing real abuse, became overly aggressive in pursuing cases based on the flimsiest of claims. The assumption that children never lied about abuse, combined with the unreliable methods used to extract statements, created a perfect storm for false accusations.

By the late 1990s, many of the wrongful convictions were overturned, and courts became more cautious about accepting testimony based on "recovered memories." But for those who had already been imprisoned, had their children taken away, or lost their reputations, the damage was irreversible. The Satanic Panic proved how fear and misinformation could warp the justice system, leaving a legacy of caution about moral panics that persists to this day.

The Decline of the Panic

By the early 1990s, cracks started to appear in the Satanic Panic narrative. Investigations into the most high-profile cases revealed a disturbing lack of evidence, and scepticism grew among journalists, legal experts, and psychologists. The same institutions that had once fuelled the hysteria began to walk back their claims, and many of those accused started to see their convictions overturned.

One of the biggest turning points came from within the scientific community. Psychologists like Elizabeth Loftus and Richard McNally published research showing how false memories could be implanted through suggestion. Studies proved that so-called "recovered memories" were unreliable, and courts became more cautious about accepting them as evidence. High-profile legal cases, such as the release of the McMartin defendants and others who had been wrongfully convicted, further exposed the flawed reasoning behind the panic.

Journalists also started questioning the stories they had once helped spread. Major media outlets that had sensationalised Satanic ritual abuse claims now published investigations debunking them. A 1995 Frontline documentary, In Search of Satan, thoroughly dismantled many of the claims that had driven the panic in the US. In the UK, similar exposés revealed how police and social workers had been influenced by pseudoscientific theories and religious pressure rather than hard facts.

Even law enforcement agencies that had once pushed the idea of Satanic cults began backtracking. In 1992, the FBI released a report by agent Kenneth Lanning, who had spent years investigating supposed ritual abuse cases. His conclusion was clear: there was no evidence of an organised network of Satanists kidnapping and abusing children. While individual cases of child abuse existed, they were not part of a grand conspiracy.

Despite this, the damage had already been done. Many of those falsely accused had spent years in prison, lost their families, or were permanently stigmatised. Public trust in mental health professionals, law enforcement, and the media suffered, as people realised how easily mass hysteria had led to real-world harm.

By the late 1990s, the Satanic Panic had largely faded from mainstream concern. However, its legacy lived on. The case studies and legal reforms that followed served as a warning about the dangers of moral panics, media-driven fear, and the consequences of ignoring due process in favour of hysteria.

How the Satanic Panic Changed the Public Association with Satanism

Before the Satanic Panic, the word "Satanism" was already controversial, but it was largely associated with religious rebellion, occultism, and, in some cases, theatrical shock value. Groups like Anton LaVey’s Church of Satan, founded in 1966, openly embraced the term but focused more on atheistic philosophy, individualism, and rejecting traditional Christian morality rather than actual devil worship. However, the panic of the 1980s and 1990s drastically reshaped public perception, turning "Satanism" into a synonym for child abuse, human sacrifice, and criminal conspiracy.

The hysteria cemented the idea that Satanists were part of a secret underground network committing horrific crimes. This belief had little basis in reality, but it was amplified by the media, law enforcement, and religious groups. Suddenly, anything linked to Satanism - whether music, books, or role-playing games - was seen as dangerous. Even non-religious countercultures, such as goths and heavy metal fans, were targeted as potential "Satanic influences."

For actual Satanists, particularly members of the Church of Satan, this was both frustrating and absurd. Their philosophy had nothing to do with criminal activity, ritual abuse, or conspiracy. Instead, LaVeyan Satanism was largely about self-empowerment, personal responsibility, and rejecting spiritual dogma. Other groups, such as The Temple of Set, took a more mystical approach but were still far from the bloodthirsty cults that the media had conjured up. However, the damage was done - few people were willing to separate reality from sensationalism, and for years, identifying as a Satanist could bring serious social consequences.

As the panic faded in the late 1990s, attitudes towards Satanism slowly began to shift again, and Satanist organisations became more vocal in reclaiming their image. The 21st century saw a rise in Satanic activism, with groups like The Satanic Temple (founded in 2013) using Satanic imagery to challenge religious influence in politics and promote secularism. Unlike LaVey’s Church of Satan, The Satanic Temple actively engages in political and social issues, gaining mainstream attention and redefining modern Satanism as a symbol of free speech and rebellion against religious oppression.

While some still associate Satanism with evil due to lingering cultural fears, the word no longer carries the same weight it did during the height of the panic. Today, Satanism is often seen as either a misunderstood philosophical movement or a provocative political statement rather than a secretive criminal network. However, the impact of the Satanic Panic still lingers, serving as a cautionary tale about how misinformation, fear, and mass hysteria can distort reality and ruin lives.