Who Was Gerald Gardner?

Share

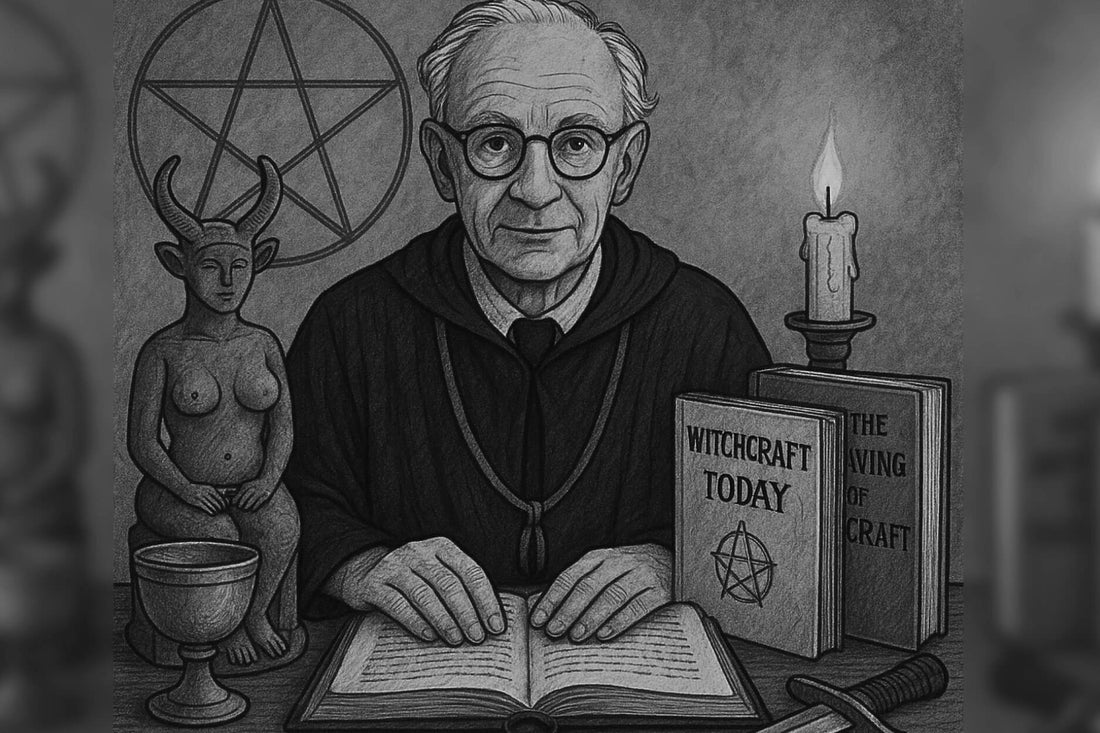

Gerald Gardner is often called the father of modern witchcraft. Whether you think he was a genuine believer, a clever showman, or something in between, his influence can’t be ignored. He took scattered ideas about folk magic, ceremonial ritual, and goddess worship, and turned them into something new: Wicca.

Before Gardner, witchcraft was mostly seen as superstition or horror-story material. After him, it had structure, symbols, books, and followers. He didn’t just practise it quietly – he wrote about it, spoke to the press, and helped pull it out of the shadows. His version of witchcraft shaped how it’s still practised today.

This article looks at who he really was. Not just the image he built, but the life he lived, the ideas he borrowed, and the legacy he left behind.

Key Points:

- Gerald Gardner is widely credited with founding modern Wicca, a structured religion that blended ritual magic, nature worship, and folk tradition.

- His version of witchcraft drew from multiple sources, including Freemasonry, ceremonial magic, and the writings of Aleister Crowley, rather than surviving ancient practices.

- Gardner claimed to be initiated into a secret group called the New Forest Coven, but there’s no firm evidence it existed before his involvement.

- He used the 1951 repeal of the Witchcraft Act to go public, publishing books and giving interviews that brought witchcraft out of the shadows and into public life.

- Though controversial, Gardner’s impact is lasting – his work shaped Wicca’s rituals, ethics, and identity, and laid the foundation for a global religious movement.

Early Life and Career

Gerald Brosseau Gardner was born in 1884 in Blundellsands, near Liverpool, into a wealthy family involved in the timber trade. He had asthma and was often sent abroad for health reasons. By the time he was a teenager, he was already spending long periods overseas, mostly in warmer climates. That pattern continued into adulthood.

In his twenties, Gardner moved to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and later to Borneo and Malaysia, working in the British colonial service. He spent most of his professional life in Southeast Asia, first as a rubber plantation manager and then as a customs officer. During that time, he became fascinated by local spiritual practices, magical rituals, and tribal religions. He collected weapons, knives, and ritual objects, many of which ended up in museums or private displays back in England.

He wasn’t formally trained in anthropology, but he acted like an amateur ethnographer. He took notes, asked questions, and built up a personal archive of spiritual beliefs from the places he lived. Some of this material later influenced the ritual structure he developed for Wicca.

After retiring in the 1930s, Gardner moved back to England. He settled in Highcliffe-on-Sea, near the New Forest, and began getting involved in local mystical and theatrical circles. That’s where his story starts to shift from traveller and collector to occultist and founder of a new religious movement.

By Sunblade1500 - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

Return to England and Occult Involvement

After returning to England in the late 1930s, Gardner didn’t settle quietly into retirement. Instead, he immersed himself in fringe spiritual groups and occult circles. He joined the Fellowship of Crotona, a Rosicrucian-inspired theatre group that performed mystical plays near the New Forest. It was there that he claimed to have encountered real practising witches.

According to Gardner, in 1939 he was initiated into a secret coven known as the New Forest Coven. The group, he said, preserved an ancient form of witchcraft that had survived persecution by passing knowledge down through generations. There’s no independent proof this coven existed, and several researchers have pointed out inconsistencies in Gardner’s account. Still, this claim became the foundation of his future work.

Around this time, Gardner also connected with Freemasons, Theosophists, and other esoteric networks. He was particularly influenced by the work of Aleister Crowley - which is one of the main connections between the occult and wicca. Although they only met a few times, Gardner absorbed elements of Crowley’s Thelemic rituals and language. These influences crept into Wicca’s structure, especially the way its rituals were written.

He didn’t just observe; he participated. Gardner saw himself as both a preserver and a reformer. He started crafting a system that combined folk magic, ceremonial ritual, and spiritual philosophy. Some parts were based on what he said he was taught by the coven. Others were clearly borrowed from existing occult texts. He edited and rewrote them, often using archaic-sounding language to make them feel older than they were.

Gardner’s mix of theatrical flair and spiritual enthusiasm attracted attention. By the late 1940s, he was already laying the groundwork for what would become known as Wicca. He wasn’t just reviving witchcraft, as he saw it – he was rebuilding it.

Founding of Wicca

By the early 1950s, Gardner was no longer just a participant in occult circles – he was positioning himself as a public authority on witchcraft. In 1951, the Witchcraft Act was repealed in the UK, removing legal barriers that had made it risky to speak openly about magical practices. Gardner wasted no time. The following year, he published Witchcraft Today, claiming it was a factual account of a surviving pre-Christian religion still practised in secret across Britain.

The book was a mix of speculation, anecdote, and recycled occult theory. He presented Wicca as a direct descendant of ancient pagan worship, even though most historians agree it was a modern construction. Gardner likely knew this. His version of witchcraft was stitched together from multiple sources: the rituals of ceremonial magic, the symbolism of the Golden Dawn, folklore, freethought, and what he said he learned from the New Forest Coven. But instead of admitting it was new, he framed it as a survival of something old.

In 1954, he followed up with The Meaning of Witchcraft. This second book laid out more detail about Wiccan philosophy and ethics. It introduced readers to concepts like the Goddess and the Horned God, the Wiccan Rede, and the idea of covens operating in secrecy. These ideas quickly spread and began to shape how people thought witchcraft worked.

Gardner’s rituals were formal and structured, often written in Elizabethan-style English to give them an air of antiquity. Tools like the athame (ritual knife), chalice, pentacle, and wand became standard. So did the casting of circles, calling of the quarters, and celebration of seasonal festivals. All of this gave Wicca a ritual system that felt old, even if much of it had been pieced together from 19th and 20th century sources.

His work didn’t go unnoticed. Some praised him for reviving interest in pagan spirituality. Others accused him of inventing a religion and pretending it was ancient. But either way, people paid attention. By the time of his death in 1964, Gardner had set in motion a movement that would grow far beyond anything he could have imagined.

By It is believed that the cover art can or could be obtained from the publisher., Fair use, Link • Fair use, Link

Gardner’s Beliefs and Practices

Gardner’s version of witchcraft introduced a full religious system, not just a collection of spells and rituals. At the centre of Wicca is a duotheistic belief: a Goddess and a God, often seen as equal and complementary forces. The Goddess is usually associated with the moon, fertility, and the earth, while the God takes on roles like the Horned God of the hunt, the sun, or the underworld. Some Wiccans take these deities literally; others treat them as symbols of nature or archetypes of human experience.

Ritual plays a huge part. Gardner promoted a structure that involved casting a sacred circle, invoking elemental forces (earth, air, fire, water), and calling on the deities. Ceremonial tools such as the athame, wand, chalice, and pentacle each had symbolic meanings and specific uses in ritual. These weren’t just props - they were part of a carefully designed system that made rituals feel purposeful and immersive.

Magic, for Gardner, was both spiritual and practical. He believed that spells worked by raising and directing energy, often through dance, chanting, or visualisation. Sex and fertility were also recurring themes, partly because of his belief in nature's cycles, and partly due to his interest in ancient mystery religions. This led to some rituals involving symbolic or actual nudity, known in Wiccan circles as working “skyclad.” It shocked some outsiders but was intended as a statement of equality and naturalness.

He also outlined an ethical code. The most famous line is the Wiccan Rede: “An it harm none, do what ye will.” It’s not a strict rule but a principle of personal responsibility. Gardner’s system also included the idea of the Threefold Law, where actions are believed to return to the practitioner three times over - good or bad. These ideas helped separate Wicca from the image of harmful or malicious witchcraft.

The ritual calendar was also important. Gardner encouraged the celebration of sabbats: seasonal festivals marking solstices, equinoxes, and cross-quarter days like Beltane and Samhain. Alongside these were esbats, held on full moons, used for spellwork or religious observance. These gatherings gave Wiccans a rhythm to follow, linking their practice to the natural world.

What Gardner created wasn’t just a new belief system – it was a full framework. It offered ritual, ethics, myth, and community to people who felt disconnected from mainstream religion. Even now, many modern Wiccans still follow the core structure he laid out, with only slight variations.

An Act against Conjurations, Witchcrafts, Sorcery and Inchantments, 1541, Parliamentary Archives • HL/PO/PU/1/1541/33H8n8

Publicity and Legal Reform

Before 1951, it was risky to talk openly about witchcraft in Britain. The Witchcraft Act of 1735 made it illegal to claim magical powers, even if you didn’t actually use them. But when that law was repealed and replaced by the Fraudulent Mediums Act, Gardner saw his chance. For the first time in centuries, it was legally safe to call yourself a witch in public. He didn’t hold back.

Gardner leaned into publicity. He spoke to journalists, gave interviews, and made regular appearances in magazines and newspapers. He used the term “witch” deliberately – partly to shock, partly to attract attention, and partly because he believed it was time to reclaim it. He presented Wicca not as a dangerous or dark force, but as a misunderstood, nature-based religion focused on peace, balance, and ancient wisdom.

He also understood the value of fiction. In 1949, before his non-fiction books, he published a novel called High Magic’s Aid under the pseudonym Scire. It disguised Wiccan rituals as part of the story, partly to avoid legal trouble and partly to test the waters. The book described magical initiations and ceremonial workings very similar to the ones he would later reveal in his public Wiccan system.

Gardner’s willingness to be the face of modern witchcraft made him stand out. Most occultists at the time were secretive. They preferred private circles and closed-door rituals. Gardner went in the opposite direction. He posed for photos, talked about covens, and made it clear that witches were no longer hiding. His efforts helped shift public perception. Witchcraft, once associated with fear and fantasy, started to seem more like a fringe religion than a criminal act.

That visibility came at a price. He was mocked by some, criticised by others, and dismissed by parts of the occult community as too flamboyant. But his strategy worked. By the early 1960s, Gardner had built a recognisable identity for Wicca. He turned it from a private belief into a growing movement. Without the 1951 legal change – and Gardner’s eagerness to use it – Wicca might have stayed underground. Instead, it stepped into the public eye.

Controversies and Criticism

Gerald Gardner’s legacy is tangled. Some see him as a religious innovator. Others call him a fabricator who stitched together bits of older traditions and passed them off as ancient witchcraft. The truth probably lies somewhere in between.

One of the biggest controversies centres around the New Forest Coven. Gardner claimed he was initiated into this group in 1939, and that it was the last remnant of a secret pagan religion that had survived the centuries underground. The problem is, there’s no solid evidence the coven existed before Gardner’s involvement. Some researchers believe it was more of a local occult theatre group that dabbled in ritual, and that Gardner either misunderstood or exaggerated their practices. Others think he invented the entire initiation story to give his new religion historical weight.

He was also accused of borrowing heavily from existing sources. Large chunks of Wiccan ritual appear to have been lifted from Aleister Crowley’s writings, Masonic rites, and ceremonial magic texts like The Key of Solomon. Gardner didn’t deny this – he often said that material had been “improved” or “rewritten” for modern use. But critics argue that his version of witchcraft was less a rediscovery and more a rebranding.

Then there’s the matter of self-promotion. Gardner enjoyed attention. He posed for photos in ritual robes, gave interviews filled with dramatic claims, and had a flair for mixing the mystical with the theatrical. Some admired his boldness. Others thought he was just looking for fame. Even inside the Wiccan community, opinions were split. Some early members felt he shared too much, too fast, and broke the secrecy they valued.

Despite these criticisms, Gardner seemed sincere in his belief. He practised what he preached, took his rituals seriously, and clearly felt Wicca filled a spiritual gap in the modern world. He may have edited history to make his religion more compelling, but he also lived it.

The debates around Gardner haven’t faded. They’ve become part of Wicca’s foundation story – complicated, disputed, but deeply influential. Whether seen as a modern myth-maker or a genuine revivalist, he forced people to think about witchcraft in a new way. That impact is hard to dismiss.

Legacy

Gerald Gardner died in 1964, but his influence didn’t stop there. By that point, Wicca had already spread well beyond his original coven. Initiates he trained, like Doreen Valiente and Raymond Buckland, helped shape and export the religion, adapting it to new audiences and cultural settings. Gardnerian Wicca, the tradition based on his original structure, became one of the most widely practised forms of modern paganism.

In the decades that followed, Wicca splintered into many branches. Some, like Alexandrian Wicca, stayed close to Gardner’s system but added new layers of ceremonial ritual. Others, like eclectic Wicca or solitary witchcraft, stripped it down and made it more personal. These newer forms often ditched formal initiation and rigid structures, but still relied on Gardner’s basic template: seasonal festivals, duotheism, circle casting, and the Rede.

Gardner also changed how people talked about witchcraft in general. Before him, the word “witch” was mostly an insult or a fantasy trope. After him, it became something people claimed with pride. His work helped reframe witchcraft as a legitimate spiritual path rather than a leftover superstition. That shift opened the door for everything from academic study to pop culture depictions to mass-market books on modern magic.

At the same time, Gardner’s legacy is still debated. Some modern witches reject the gender binary in his system. Others push back against the hierarchical structure or the ritual nudity found in early covens. His work was a product of its time – shaped by mid-20th-century British culture, colonial attitudes, and a narrow view of what religion should look like. Later generations have reworked it, challenged it, or moved past it altogether.

But no matter how the practice evolves, it still sits on Gardner’s foundation. He didn’t just invent Wicca – he made space for it to grow. Without him, there might be no global Wiccan community, no festivals, no endless shelves of spellbooks in high street shops. His vision was flawed, controversial, and occasionally theatrical – but it was also enduring. Gardner didn’t revive an old idea, instead he really created something new that people still live by today.