Where Did Satanism Come From?

Share

Satanism is one of the most misunderstood belief systems in history. Many people hear the word and immediately think of devil worship, black magic, or secret cults performing dark rituals. But the reality is far more complex. Satanism is not a single, unified religion. Instead, it’s a collection of different philosophies, ideologies, and spiritual movements that have evolved over centuries. Some forms of Satanism are theistic, meaning they believe in and worship Satan as a deity. Others, like LaVeyan Satanism, are entirely atheistic, using Satan as a symbol of rebellion, individualism, and rational thought rather than as a literal being.

The confusion surrounding Satanism is largely due to centuries of religious propaganda, cultural myths, and moral panics. From medieval witch hunts to the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, fear and misinformation have shaped public perception far more than actual Satanic beliefs or practices.

This article explores where Satanism came from, tracing its roots from ancient religious texts to modern-day political activism. By understanding its history, we can separate myth from reality and see how a figure once feared as the ultimate evil became, for some, a symbol of freedom and defiance.

The Biblical and Religious Foundations

The origins of Satanism are deeply tied to the evolution of Satan as a religious figure. Contrary to popular belief, Satan did not start as the red-skinned, horned ruler of hell seen in modern depictions. His earliest appearances in religious texts paint a much more nuanced picture.

In the Hebrew Bible, the word Satan (שָׂטָן) simply means “adversary” or “accuser.” It wasn’t a specific being at first - rather, it referred to any opponent or even a divine figure acting on God’s behalf. In the Book of Job, for example, Satan is not an independent force of evil but a member of God’s heavenly court, testing Job’s faith under divine permission. This idea of Satan as a challenger rather than an enemy is a far cry from the Christian concept of the devil.

It wasn’t until later Jewish and Christian writings that Satan evolved into a more sinister character. By the time of the New Testament, particularly in books like Revelation, Satan had become a rebellious fallen angel waging war against God. Early Christian writers took this further, linking Satan with Lucifer - a name derived from a passage in Isaiah that originally referred to the Babylonian king but was later reinterpreted as a reference to the devil.

As Christianity spread, the idea of Satan as a powerful, malevolent being took hold. By the Middle Ages, Christian theology had firmly established Satan as the ruler of hell, the tempter of humanity, and the ultimate force of evil. This shift laid the groundwork for later fears of devil worship and Satanic cults - fears that would lead to brutal witch hunts and accusations of heresy for centuries to come.

These religious foundations didn’t just define Satan; they also influenced how Satanism would later develop. Over time, people would take the concept of Satan and reinterpret it - not as a force of evil, but as a symbol of resistance, knowledge, and personal freedom.

Satanism in Folklore and Witch Hunts

By the Middle Ages, Satan was no longer just a theological concept - he had become a figure of terror woven into European folklore. The Christian Church’s growing influence meant that anything perceived as opposing its teachings could be labeled as “Satanic.” This fear led to widespread paranoia, fueling witch hunts, executions, and accusations of devil worship that shaped the perception of Satanism for centuries.

One of the key moments in this transformation was the publication of the Malleus Maleficarum (“The Hammer of Witches”) in 1487 by Heinrich Kramer, a Dominican inquisitor. This book laid out the supposed connection between witches and Satan, arguing that witches made pacts with the devil, performed dark rituals, and used magic to harm others. Though widely discredited today, it became a handbook for witch hunters across Europe and played a central role in the execution of thousands of people - mostly women - accused of practicing Satanic witchcraft.

During this period, the idea of secret Satanic cults began to take shape. People believed witches gathered at night in forests or remote locations for Sabbats, where they supposedly worshipped Satan, sacrificed children, and took part in wild, blasphemous orgies. None of this was ever proven, but the fear was so strong that thousands were tortured and executed based on little more than rumours and forced confessions.

The hysteria wasn’t limited to Europe. The infamous Salem Witch Trials of 1692 in colonial America were driven by similar fears of hidden Satanic activity. Over 200 people were accused, and 20 were executed, despite no real evidence that any of them had engaged in devil worship.

These witch hunts cemented the link between Satan and secret, sinister groups - a narrative that would resurface in later centuries, particularly during the Satanic Panic of the 20th century. But they also unintentionally helped shape modern Satanism. The very things that Christian authorities feared - rituals, independence from the church, and defiance of religious norms - would later become key themes in actual Satanic philosophy. Instead of fearing Satan, some people began embracing him as a symbol of rebellion against oppressive religious dogma.

While the medieval image of Satanic cults was largely a myth, it helped create a framework for what people would later call Satanism. The idea of worshipping the devil may have been an invention of the church, but over time, it would inspire real movements that turned Satan into something far more than just a villain in Christian doctrine.

Romanticism and the Rise of the Rebel Satan

By the 17th and 18th centuries, the fear of literal devil worship began to fade in intellectual circles. The Enlightenment brought a wave of rational thought that challenged the grip of religious dogma, and in the process, some began to reimagine Satan - not as an evil tempter, but as a tragic, defiant figure resisting tyranny.

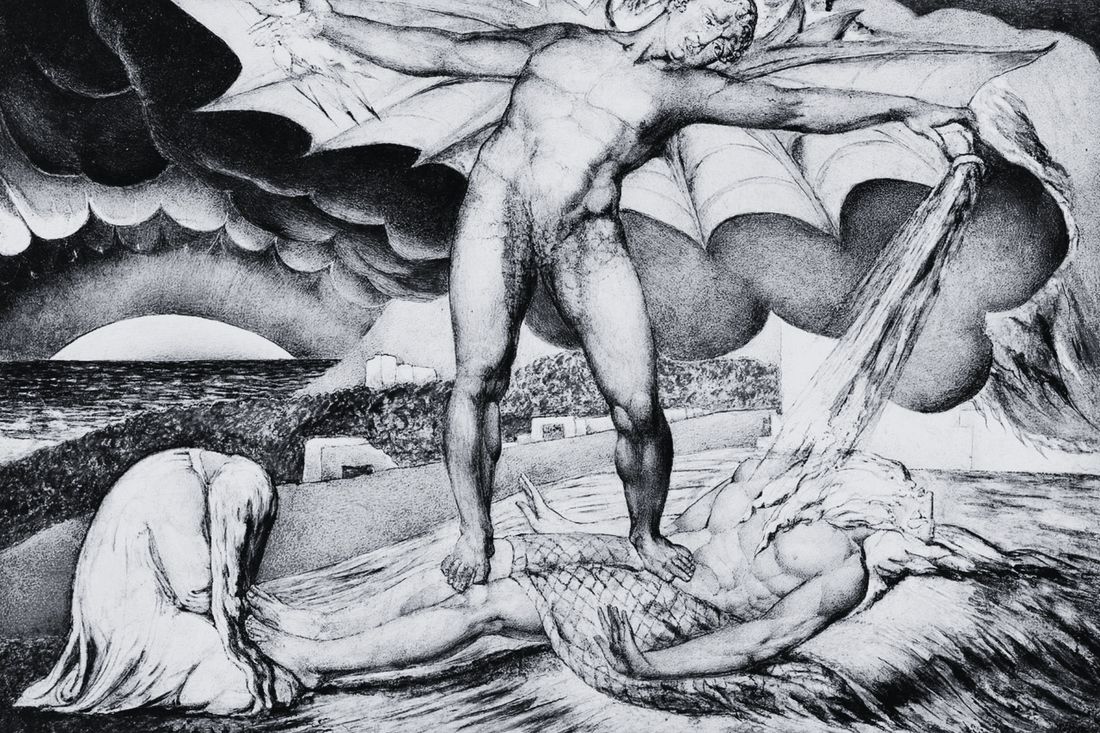

One of the most influential works in this transformation was John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667). Though Milton was a devout Christian, his portrayal of Satan was surprisingly sympathetic. Instead of a mindless force of destruction, Milton’s Satan was charismatic, intelligent, and fiercely independent. His famous line, "Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven," captured the essence of rebellion, turning him into an antihero rather than just a villain. Romantic poets like Lord Byron and Percy Bysshe Shelley took this even further. They saw Milton’s Satan as a symbol of defiance against authority, much like Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods in Greek mythology.

By the 19th century, this literary Satan had become a powerful symbol for those who opposed oppressive institutions, particularly the church and monarchy. Figures like William Blake even suggested that Satan represented true human freedom, while God symbolised control and repression. This was a radical shift - Satan was no longer just an object of fear but a symbol of resistance, intellect, and self-determination.

This reinterpretation didn’t stay confined to poetry and literature. Occult groups and secret societies of the time, such as the Freemasons and the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, incorporated Satanic imagery into their mystical philosophies. Some, like the notorious British occultist Aleister Crowley, embraced Satan as a metaphor for breaking free from religious and moral constraints. Crowley’s infamous motto, “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law,” echoed the Romantic-era idea of Satan as a liberator rather than a destroyer.

While these movements weren’t Satanist in the modern sense, they laid the foundation for what would come next. The idea of Satan as an individualistic, rebellious force directly influenced 20th-century Satanism, particularly the version promoted by Anton LaVey. By the mid-20th century, Satan had evolved from a religious villain into a philosophical symbol - one that would soon become the core of an organised Satanic movement.

The Birth of Modern Satanism

The 20th century saw Satanism move from scattered occult influences and literary interpretations into an organised movement. The most significant turning point came in 1966 when Anton LaVey founded the Church of Satan in San Francisco. For the first time, Satanism was not just an accusation made by religious authorities - it was a self-proclaimed philosophy with a structured set of beliefs.

LaVey’s version of Satanism was not about devil worship. In fact, LaVeyan Satanists don’t believe in Satan as a literal being at all. Instead, they see Satan as a symbol of individualism, personal power, and defiance against religious control. In The Satanic Bible (1969), LaVey outlined his philosophy, drawing from sources like Friedrich Nietzsche, Ayn Rand, and social Darwinism. His Satanism was hedonistic and self-focused, promoting indulgence rather than abstinence, and rejecting guilt imposed by traditional religions.

The Church of Satan’s rituals were largely theatrical, meant more for psychological effect than supernatural power. LaVey borrowed heavily from occult imagery, but his goal was to create a religion that celebrated human instincts rather than suppressing them. The infamous Black Mass, often associated with Satanism, was used more as a mockery of Christian traditions than as an actual religious rite.

Around the same time, another form of Satanism was emerging - one that did involve literal belief in Satan as a deity. Theistic Satanists, unlike LaVeyan Satanists, view Satan as a real spiritual being worthy of worship. These groups vary widely, from those who see Satan as a misunderstood god of wisdom to those who embrace a darker, more ritualistic approach. Some of these ideas were influenced by earlier occult movements, such as Aleister Crowley’s Thelema and the mystical teachings of the 19th-century Hermetic revival.

While LaVeyan Satanism gained the most attention in mainstream culture, the rise of theistic Satanism contributed to the perception that Satanism was dangerous. Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, sensationalist media reports exaggerated claims of Satanic rituals, reinforcing the idea that Satanists were engaged in criminal or supernatural activities.

By the end of the 20th century, Satanism had solidified into distinct movements: LaVeyan Satanism, which was atheistic and symbolic, and theistic Satanism, which viewed Satan as an actual deity. Both versions continued to grow, but it was the next major cultural panic - the Satanic Panic of the 1980s and 1990s - that would once again push Satanism into the public spotlight, this time through fear and hysteria.

The Satanic Panic and Cultural Shifts

The 1980s and early 1990s saw a wave of hysteria sweep across the United States and parts of Europe, driven by the belief that secret Satanic cults were committing widespread crimes, including ritual abuse, child sacrifice, and even murder. This period, known as the Satanic Panic, was fuelled by a mix of sensationalist media, religious fundamentalism, and flawed psychological theories. It remains one of the most infamous moral panics in modern history.

The panic began with a combination of high-profile cases, dubious testimonies, and exaggerated media reports. Books like Michelle Remembers (1980) claimed to expose horrifying Satanic rituals, though its content was later discredited. Sensational talk shows, evangelical preachers, and law enforcement training materials spread the idea that organised Satanic cults were operating in secret, brainwashing children, and performing grotesque rituals.

One of the most damaging aspects of the Satanic Panic was the rise of “recovered memory therapy,” a controversial psychological practice that led many patients to falsely believe they had been victims of Satanic abuse. As a result, hundreds of people were falsely accused, and numerous daycare workers, teachers, and parents were put on trial with little to no evidence. The McMartin preschool trial (1983–1990) became one of the longest and most expensive criminal trials in U.S. history, with accusations of underground tunnels, animal sacrifices, and Satanic ceremonies - all of which were ultimately proven false.

Despite the lack of credible evidence, law enforcement agencies and courts took these claims seriously, leading to wrongful convictions and ruined lives. Heavy metal music, role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons, and even horror movies were blamed for corrupting youth and leading them toward Satanism. The image of Satanism presented during this period was almost entirely fictional, but it had a lasting impact on public perception.

By the mid-1990s, investigations into the so-called Satanic cult network found no solid proof of widespread ritual abuse. Scholars, journalists, and legal experts exposed the panic as a mix of mass hysteria, pseudoscience, and religious paranoia. However, the damage was done - Satanism had been deeply associated with crime and perversion in the public mind, even though real Satanic groups had little to do with the crimes they were accused of.

This period also shaped modern Satanism in unexpected ways. The Church of Satan distanced itself from criminal accusations, while new groups, such as The Satanic Temple, emerged in the 2010s to challenge the lingering effects of the panic. Instead of hiding, these new Satanic organisations leaned into political activism, using Satanic imagery to fight for religious freedom, secularism, and personal rights.

The Satanic Panic ultimately proved to be built on fear and misinformation, but it reinforced Satanism’s role as a symbol of rebellion. It also demonstrated the power of mass hysteria, showing how quickly society can be swept up in paranoia when fear overrides reason. While the panic eventually faded, its influence lingers in conspiracy theories, religious rhetoric, and popular culture.

Satanism Today

Satanism has evolved significantly since its medieval associations with devil worship and the hysteria of the Satanic Panic. Today, it exists in multiple forms, with some groups embracing it as a religious identity and others using it as a political statement. Modern Satanism is far more focused on philosophy, activism, and cultural symbolism than on supernatural beliefs or secret rituals.

The two most prominent branches of Satanism today are LaVeyan Satanism and The Satanic Temple. The Church of Satan, founded by Anton LaVey in 1966, continues to promote a philosophy of individualism, rational self-interest, and rejection of traditional religious morality. Though it has largely distanced itself from public activism, it remains influential in the world of modern Satanism, particularly through The Satanic Bible and its associated literature.

In contrast, The Satanic Temple (TST), founded in 2013, has taken Satanism in a more politically active direction. Unlike the Church of Satan, which avoids direct engagement with politics, TST uses Satanic imagery to advocate for secularism, free speech, and the separation of church and state. One of its most famous campaigns involved erecting a statue of Baphomet in response to Ten Commandments monuments on government property, arguing that if Christian symbols were allowed in public spaces, so should Satanic ones.

The Satanic Temple also fights for reproductive rights, LGBTQ+ equality, and religious freedom, using Satanic iconography to challenge Christian fundamentalist influence in government policies. However, like LaVeyan Satanists, members of TST do not actually worship Satan. Instead, they see Satan as a symbol of rebellion against tyranny, dogma, and oppression.

Beyond these major organisations, there are also smaller groups of theistic Satanists, who believe in Satan as a real spiritual entity. These groups vary widely in beliefs, from those who view Satan as a misunderstood deity of wisdom to those who adopt darker, more esoteric rituals. However, these groups are far less common than atheistic or symbolic forms of Satanism.

Satanism’s influence extends into popular culture as well. Heavy metal and gothic subcultures have long embraced Satanic imagery, often as a form of artistic rebellion rather than genuine belief. Horror films, video games, and literature frequently reference Satanism, sometimes reinforcing old myths and other times challenging them.

While Satanism remains controversial, its modern practitioners are far from the devil-worshipping cultists that past generations feared. Today’s Satanists are more likely to be political activists, free-thinkers, and secularists than occultists summoning demons. The movement continues to challenge mainstream religious narratives and provoke discussions on freedom, morality, and personal autonomy.

Satanism has undergone a remarkable transformation over the centuries. What began as a religious adversary in ancient texts evolved into a symbol of rebellion, individualism, and political activism. From its roots in biblical mythology to its reinvention in literature, philosophy, and organised movements, Satanism has continuously adapted to the cultural and social landscape of its time.

During the Middle Ages, fear of Satan led to witch hunts and mass hysteria, shaping the perception of Satanism as something inherently evil. The Romantic era reframed Satan as a figure of defiance, influencing later occultists and philosophers who saw him as a representation of human freedom. By the 20th century, Anton LaVey turned Satanism into an official movement, stripping it of supernatural elements and focusing instead on self-empowerment and personal autonomy.

The Satanic Panic of the 1980s reinforced many misconceptions about Satanism, associating it with crime and ritual abuse despite the lack of evidence. But in the 21st century, Satanism has become more visible, with groups like The Satanic Temple using it as a tool for political activism and religious freedom. While some still hold to theistic beliefs, modern Satanism is largely about challenging religious dogma and celebrating rational thought, individualism, and personal responsibility.

Whether viewed as a serious religious movement, a political statement, or an artistic expression, Satanism continues to provoke, challenge, and evolve. It remains one of the most misunderstood yet culturally significant belief systems in the world. While the myths surrounding it persist, today’s ‘Satanists’ are more likely to be found in courtrooms defending secularism than in basements performing dark rituals. Satanism’s history is ultimately one of transformation - from feared heresy to an ideology that questions authority and champions personal freedom.