Is the Book of Shadows the Wiccan Holy Book?

Share

A question that almost always comes up whenever Wicca is discussed, especially by those looking in from the outside, is “Is there a Wiccan holy book?”. Is there a single, leather-bound tome, a "Wiccan Bible," that sits on every witch's altar, dictating law, liturgy, and belief?

The short answer, which is both simple and profoundly revealing, is no. There isn't one.

The long answer, however, unwraps the very soul of the Wiccan religion. It explains why a faith that has grown so rapidly in the modern world actively resists the idea of a central, unchanging scripture. The journey to understand this "no" takes us through the nature of personal experience, the secret history of modern witchcraft, and into the pages of a witch's most prized possession: the Book of Shadows. This book is not a scripture handed down from on high. It is something far more intimate, dynamic, and, to the practitioner, infinitely more powerful.

Key Points

- Wicca rejects the idea of a single holy book, instead valuing direct personal experience with the divine over fixed scripture.

- The Book of Shadows is a witch’s personal record, blending rituals, spells, ethics, and diary entries into a living, evolving text.

- Wicca’s modern roots, shaped by figures like Gerald Gardner and Doreen Valiente, mean it grew without central authority, allowing diverse traditions to flourish.

- Influential works by writers such as Scott Cunningham, Starhawk, and Raymond Buckland spread Wicca globally, but none are treated as infallible scripture.

Why No Central Scripture? A Religion of Experience, Not Text

To grasp why Wiccans don’t have a holy book, you must first throw out your assumptions about what a religion is supposed to look like. The major world religions, particularly the Abrahamic faiths of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam, are often called "religions of the book." Their foundation is built upon a body of sacred texts believed to be divinely inspired. A prophet or holy figure receives wisdom from God, this wisdom is written down, and that text becomes the ultimate authority on truth, morality, and how to live. The follower's role is to read, to have faith in, and to follow the doctrines laid out in those pages.

Wicca flips that entire model on its head. It is, at its core, a religion of experience, not of text. It prioritises gnosis - a direct, personal, and intuitive knowing of the divine - over pistis, which is faith in a received doctrine. Think of it like this: reading a restaurant menu is not the same as tasting the food. The Abrahamic faiths, in a way, ask you to trust that the menu is an accurate and perfect description of the meal. Wicca tells you to get into the kitchen and start cooking for yourself.

The central focus of the Wiccan path is the individual’s direct, unmediated connection with the divine. This divinity is typically seen as immanent, meaning it exists within the world, not separate from it. Wiccans generally worship a God and a Goddess, powerful archetypes who are manifest in the cycles of nature and within our own consciousness. The goal isn't to read about someone else’s spiritual encounter from two thousand years ago; it’s to have your own, right now, in your own back garden. It’s about feeling the first warmth of the spring sun on your skin, watching the full moon rise over the rooftops, and finding the sacred in the tangible, living world. A single, static book, written by men in a distant past, could never capture that vibrant, ever-changing reality. In my opinion, it would be a cage for a faith that is meant to be wild.

Furthermore, Wicca is a fundamentally modern and decentralised religion. While its practitioners draw inspiration from ancient pagan beliefs, folklore, and ceremonial magic, the religion of Wicca itself was formally established in England in the mid-20th century. Its founder was a retired British civil servant and amateur anthropologist named Gerald Gardner. He cobbled together elements from Freemasonry, the writings of Aleister Crowley, folk magic traditions, and the (now largely discredited) historical theories of Margaret Murray to create the structure of modern Wicca. It was born not from a single, grand revelation, but from an eclectic mix of influences.

Because it grew out of small, secret groups called covens, there was never a central authority. There is no Wiccan Pope, no Vatican, no council of elders to declare one book as the "one true word." This lack of a central power structure is a defining feature. It has allowed the religion to diversify into dozens of different "traditions" - Gardnerian, Alexandrian, Dianic, Reclaiming, and more - each with its own subtle variations in practice and belief. A single holy book would be impossible because there is no single, monolithic "Wicca" for it to represent.

Photo by RDNE Stock project: https://www.pexels.com/photo/close-up-shot-of-a-spell-book-and-a-wand-7978237/

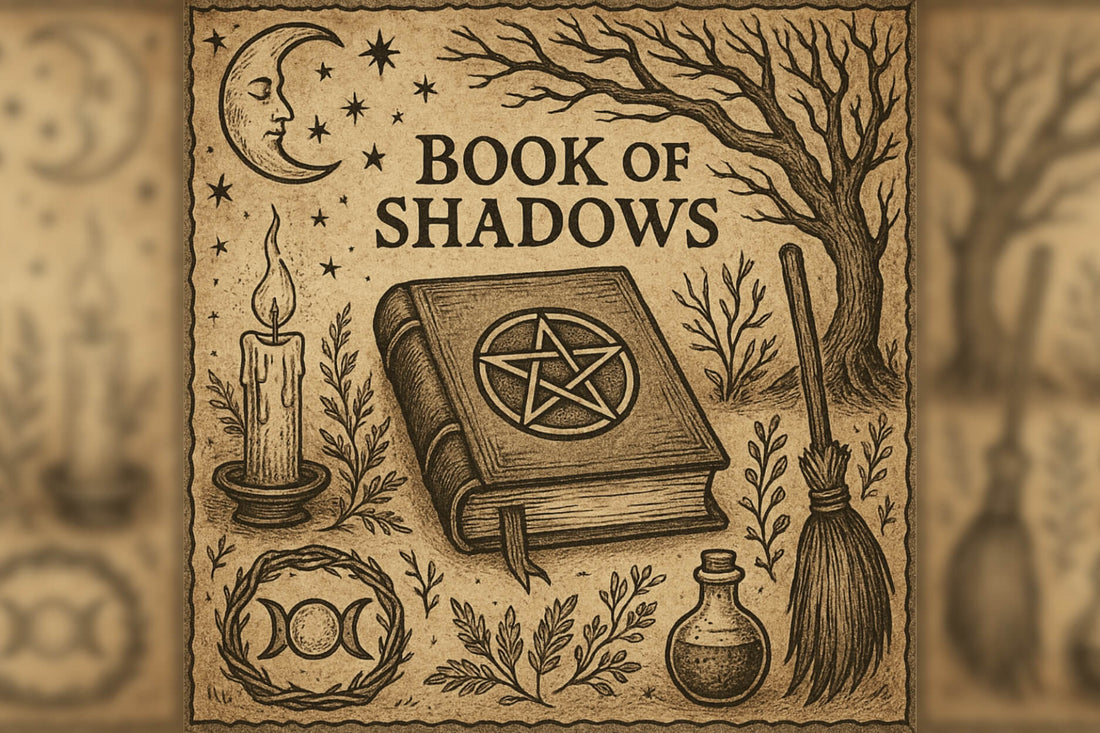

The Book of Shadows

So, if there’s no Bible, what do Wiccans use? They use a Book of Shadows.

A Book of Shadows, often shortened to BOS, is a witch’s personal magical journal. It is a workbook, a diary, a recipe book for spells, and a spiritual autobiography all rolled into one. It is, without a doubt, the most sacred object a Wiccan practitioner owns. Its sacredness comes not from a divine author, but from the fact that it is created, curated, and consecrated by the witch themselves. It is a living document that records their unique path, their hard-won knowledge, their successes, and their informative failures. It grows, changes, and deepens as they do.

The term was popularised by Gerald Gardner. He and his High Priestess, the formidable and brilliant Doreen Valiente, compiled a Book of Shadows for their original coven. This book contained their core rituals, spells, and the foundational mythology of their tradition. Valiente, a gifted poet, found Gardner's original writing to be somewhat dry and academic. She famously rewrote vast sections of it, transforming it into the beautiful and powerful ritual liturgy that is still used today. Her most famous contribution, a piece of prose called "The Charge of the Goddess," is a perfect example. It begins:

"Listen to the words of the Great Mother, who was of old also called among men Artemis, Astarte, Athene, Dione, Melusine, Aphrodite, Cerridwen, Dana, Arianrhod, Isis, Bride, and by many other names."

This single piece of writing is perhaps the closest thing to a universally beloved text in Wicca, yet it is part of a larger, adaptable collection, not a standalone holy book.

In those early days, when a new person was initiated into a traditional coven, they would have to painstakingly copy the coven’s master Book of Shadows by hand into their own blank book. This was a crucial part of the training. It forced the student to engage deeply with every word, every symbol. It was an act of devotion and a rite of passage. The new initiate was then expected to add their own material to their personal copy - new spells they’d created, records of their divination, poetry, or personal insights. The book was both a received tradition and a personal journal.

What Lies Within the Shadows?

The contents of a Book of Shadows are as varied as the witches who keep them, but they generally contain several key sections:

- Laws and Ethics: Many begin with a foundational text, such as the Wiccan Rede ("An it harm none, do what ye will") or other ethical guidelines like the Threefold Law (the belief that the energy you send out, positive or negative, returns to you threefold). The witch will often write their own commentary on what these laws mean to them in practice.

- Rituals: This is the heart of the book. It contains step-by-step instructions for religious rites. This includes the eight Sabbats, the seasonal festivals that mark the turning of the Wheel of the Year (Samhain, Yule, Imbolc, Ostara, Beltane, Litha, Lughnasadh, and Mabon). It also includes instructions for Esbats, the regular rituals held on the full or new moon. A typical ritual structure might be detailed here: how to prepare, how to cast a magical circle, how to call the elemental quarters, how to invoke the God and Goddess, the main body of the working, the simple feast of "Cakes and Ale," and how to properly thank the divine and close the circle.

- Spells and Workings: This is the "magic" section. It’s a collection of magical recipes. These can range from simple folk charms (like tying a knot in a cord while focusing on an intention) to complex, multi-day spells for things like healing, prosperity, or protection. Each entry might include the purpose of the spell, the ingredients needed (herbs, candles, oils), the best time to perform it (such as a specific moon phase or day of the week), and the incantation or words to be spoken.

- Correspondences: These are the witch’s essential reference charts. They are long lists that connect various items to magical intentions. For example, a "Prosperity" correspondence table might list: the colour green, the planet Jupiter, the herb basil, the crystal citrine, and the number four. These tables are vital tools for designing effective spells and rituals from scratch.

- Deity Information: Wiccans are polytheists, and a witch will often dedicate sections of their BOS to the specific deities they feel a connection to. This might include myths and stories about the god or goddess, their known symbols, offerings they appreciate, and personal records of meditations or interactions with that deity. You might find pages dedicated to figures like Hecate, Cernunnos, Brigid, or Pan.

- The Personal Diary: This is arguably the most important part. It is where the witch records the results of their work. Did that spell work? How did that tarot reading play out in real life? What strange dream did they have after a ritual? What did they learn from a mistake? This section transforms the BOS from a static reference book into a dynamic tool for self-reflection and spiritual growth. It is the witch’s spiritual autobiography in real-time.

The Coven Book vs. The Solitary’s Grimoire

The nature of the Book of Shadows has evolved. In traditional, initiatory Wicca (like the Gardnerian and Alexandrian traditions), the BOS is "oath-bound." An initiate swears never to show their book to a non-initiate. The core rituals and secrets are passed down in a direct line from teacher to student.

However, the vast majority of people who identify as Wiccan today are not members of a traditional coven. They are "solitary practitioners." For a solitary, the Book of Shadows is a completely personal creation from the ground up. It might be a beautiful, handcrafted journal with an embossed pentacle, or it could be a simple spiral notebook. Many modern witches even use digital formats like a password-protected document or a private blog, valuing the searchability and portability.

The solitary witch faces both a great freedom and a great challenge. The freedom is to build a spiritual path that is 100% authentic to them, drawing from any source that resonates. The challenge is the lack of a teacher, which requires immense self-discipline and discernment to sort credible information from the misinformation that is rife online. Their Book of Shadows becomes the testament to this personal quest, a map they have drawn for themselves through the wilderness of magical information.

|

|

|

|

The Influential Books That Built a Movement

While there is no single holy book, it would be wrong to say that published books are not important to Wiccans. In fact, a small library of influential works has been so foundational that they have effectively shaped the entire modern pagan movement. These aren't seen as infallible scriptures, but as the essential textbooks and guides that have educated generations of practitioners.

- "Witchcraft Today" (1954) & "The Meaning of Witchcraft" (1959) by Gerald Gardner: These are the books that launched the ship. Gardner introduced the world to his version of the "Old Religion," setting the stage for everything that followed.

- "The Rebirth of Witchcraft" (1989) by Doreen Valiente: Valiente’s own account of the early days of Wicca is an essential historical document. It provides a first-hand perspective on the creation of the religion and corrects many of the myths that had grown up around Gardner.

- "Buckland's Complete Book of Witchcraft" (1986) by Raymond Buckland: Affectionately known as the "Big Blue Book," this was a revelation. Buckland, a Gardnerian initiate, created a comprehensive, step-by-step "course in a book." With lessons, exercises, and Q&As, it systematically taught the fundamentals of the craft to anyone with the price of a paperback.

- "Wicca: A Guide for the Solitary Practitioner" (1988) by Scott Cunningham: This book is arguably the single most important reason for Wicca’s explosive growth in the late 20th century. Cunningham presented a gentle, nature-focused, and accessible form of the religion that did not require coven initiation. He democratised the craft, empowering hundreds of thousands of people to begin their practice alone. His work was so popular that by 2001, it was reported that his books accounted for a huge portion of all pagan book sales, a testament to his profound impact (Clifton, S. & Harvey, G., The Paganism Reader, 2004).

- "The Spiral Dance" (1979) by Starhawk: Starhawk’s masterpiece did for feminist spirituality what Cunningham’s did for solitary practice. She brilliantly wove together Wiccan practice with deep ecology, feminist politics, and social activism. She presented magic not just as a tool for personal change, but for healing the world. Her work inspired the influential Reclaiming tradition of witchcraft.

- "A Witches' Bible" by Janet and Stewart Farrar (1996): The Farrars, initiates in the Alexandrian tradition, published their coven's complete Book of Shadows. This gave non-initiates an unprecedented look at a full, working system of traditional Wiccan ritual. It became a foundational text for countless non-traditional covens and solitaries who wanted a more formal, ceremonial structure.

These books are revered as the work of respected elders and pioneers. But they are not gospel. A Wiccan can, and often does, read them, take what works, discard what doesn’t, and adapt the material for their own use. This critical engagement is a core part of the modern witch’s path.

Conclusion: The Scripture is Written in Wind and Stone

So, we return, finally, to our simple question. Is there a Wiccan holy book? No. And that absence is not a lack; it is a statement of principle. It is the religion’s greatest strength.

Wicca does not lock the divine away between the covers of a single book. It does not demand faith in ancient words. Instead, it pushes you out of your chair and into the world, demanding that you find the sacred for yourself. The true Wiccan scripture is written in the patterns of migrating birds, the scent of rain on dry earth, the power of a raging bonfire, the quiet light of the full moon, and the unshakeable turning of the seasons.

The Book of Shadows is the precious and personal tool that helps you learn to read that living scripture. It is your map, your lab notebook, your confidant, and your spiritual legacy. It is sacred not because of who wrote it centuries ago, but because of what it represents right now: your own, unique, and hard-won conversation with the universe. It is a testament to a faith that values questions over answers, experience over doctrine, and personal responsibility over blind obedience. And that is a kind of holiness that no single, printed book could ever hope to contain.