What Is The Wheel of The Year?

Share

The Wheel of the Year is one of those ideas that sounds ancient, mystical, and timeless - but the truth is messier. It’s a blend of old seasonal festivals and modern Pagan invention, stitched together in the mid-20th century and polished until it gleams like something eternal. Wiccans and Pagans often talk about it as if it’s always been there, turning steadily for millennia. In reality, it’s part historical revival, part creative reimagining, and part spiritual tool. That mix is exactly what makes it powerful.

If you want the full lowdown on each of the eight festivals - their histories, rituals, and personal meaning - I’ve already covered that elsewhere in our article on the Eight Sabbats of Wicca. But here, the focus is different. This is about the Wheel itself: what it is, where it came from, what it symbolises, and how people use it today.

Key Points

- The Wheel is Modern, Not Ancient – The eightfold cycle was shaped in the mid-20th century by Gerald Gardner and Ross Nichols, combining Celtic fire festivals with solstices and equinoxes. Its structure is recent, though its roots are older.

- It Symbolises Cyclical Time – Unlike Christianity’s linear timeline, the Wheel frames existence as a cycle: death feeds life, darkness gives way to light, and every ending carries the seed of renewal.

- Eight Festivals, Many Practices – The Wheel maps eight seasonal markers, but not all Pagans celebrate all of them. Rituals range from formal ceremonies to small personal gestures, adaptable to city or countryside.

- Flexible, Not Fixed – While some criticise its modernity, Eurocentric bias, or risk of rote repetition, the Wheel’s strength lies in its adaptability. It works as myth, metaphor, spiritual calendar, or mindfulness tool.

The Origins of the Wheel

The Wheel of the Year didn’t fall fully formed from some dusty grimoire. Its bones are ancient, yes, but its flesh is new. To understand it, you need to look at two threads that were tied together by modern Pagans: the Celtic fire festivals and the solar festivals of solstice and equinox.

The Celtic fire festivals - Imbolc, Beltane, Lughnasadh, and Samhain - were agricultural markers tied to livestock, planting, and harvest. They appear in early Irish sources, sometimes with ritual fire, sometimes with feasting, sometimes with barely a trace beyond the name. These festivals were local and practical, not a neat system.

Then there are the solstices and equinoxes. These mattered across many cultures, from Stonehenge alignments to Roman calendars. They track the sun’s extreme points: longest day, shortest day, equal day and night. Unlike the fire festivals, these aren’t specifically Celtic - they’re universal markers of time.

In the 1950s, two men - Gerald Gardner, founder of Wicca, and Ross Nichols, founder of the Order of Bards, Ovates and Druids - pulled the two sets together. Gardner emphasised the solar festivals. Nichols loved the Celtic fire days. Between them, the eightfold Wheel was born. Later, Aidan Kelly in the 1970s gave modern names to some of the sabbats, like Ostara and Mabon, cementing the wheel-shaped calendar Wiccans know today.

So, the Wheel of the Year is not an unbroken tradition. It’s a 20th-century construction. But that doesn’t make it less powerful. Every religion invents traditions. What matters is that this one works - it ties seasonal shifts to spiritual meaning, giving modern practitioners a rhythm to live by.

Photo by İbrahim Hakkı Uçman: https://www.pexels.com/photo/four-leaves-on-wooden-board-691067/

Cyclical Time vs Linear Time

The real genius of the Wheel isn’t the eight festivals themselves - it’s the shape. A circle. A cycle. A reminder that time doesn’t just run like a straight line from birth to death.

Most of Western religion, particularly Christianity, deals in linear time. The universe is created, life marches forward, history unfolds, and eventually there’s an ending - apocalypse, judgement, the end of days. Linear time has a destination.

The Wheel rejects that. It says time is cyclical: light returns after darkness, life springs up after death, and endings are always beginnings in disguise. That’s not a romantic gloss; it’s what nature shows us. Trees shed, fields rest, seeds rot - and out of that decay comes new growth. The Wheel is nature’s clock.

This cyclical view changes how practitioners see themselves. Death isn’t the end; it’s a turning point. Loss isn’t a collapse; it’s part of a pattern. Rebirth isn’t a miracle; it’s inevitable. In a culture obsessed with progress and deadlines, the Wheel offers a radical idea: slow down, notice the cycle, accept the turning.

Structure of the Wheel

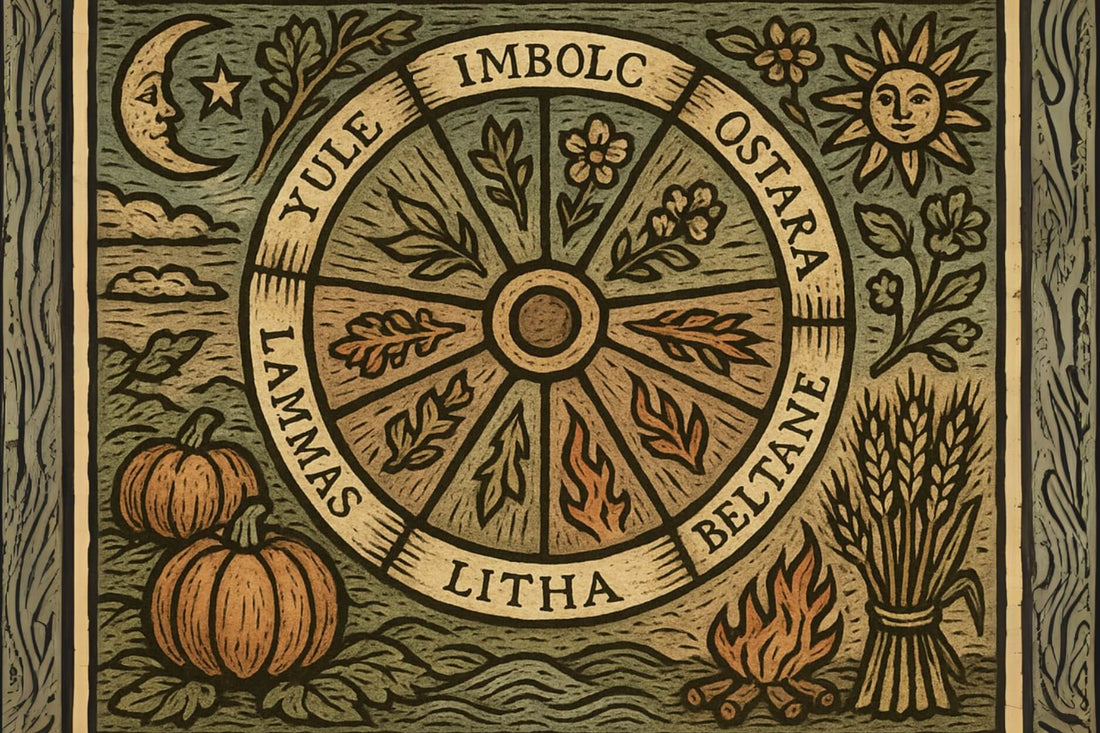

The Wheel is made up of eight festivals spaced roughly six to seven weeks apart. Four of these are solar events:

- Yule (Winter Solstice, ~21 December)

- Ostara (Spring Equinox, ~20 March)

- Litha (Summer Solstice, ~21 June)

- Mabon (Autumn Equinox, ~21 September)

And four are cross-quarter days, falling between them:

- Imbolc (~1 February)

- Beltane (~1 May)

- Lughnasadh / Lammas (~1 August)

- Samhain (~1 November)

This eightfold structure is neat, regular, and easy to map. But don’t mistake neatness for dogma. Not all Pagans observe all eight, and some stick to the four Celtic festivals. Others focus on solstices and equinoxes. In the Southern Hemisphere, the dates are flipped six months, so Yule falls in June and Samhain in May. The wheel isn’t fixed you see; it adapts to the land you live on.

Symbolism of the Wheel

The festivals are one thing; the myths layered over them are another. Wiccans in particular see the Wheel as a cosmic story told in eight chapters.

The Oak King and Holly King

In one popular myth, two kings battle for dominance across the year. The Oak King rules from midwinter to midsummer, growing stronger as the light returns. The Holly King rules from midsummer to midwinter, drawing strength as the nights lengthen. Each defeats the other in turn, a perpetual exchange of power. It’s a simple story of balance: light and dark chasing each other endlessly.

The God and Goddess Cycle

Another Wiccan interpretation frames the Wheel as the life cycle of the God, mirrored by the Goddess. At Yule, the God is born. At Beltane, he and the Goddess unite. At Litha, he is at full power. By Lughnasadh, he begins to decline, and by Samhain, he dies, only to be reborn again at Yule. The Goddess, constant through the seasons, embodies the Earth and the cycle itself.

These myths aren’t literal though, they’re symbolic. They map human experience (birth, growth, love, decline, death) onto the natural seasons. The wheel turns in the sky, and in our own lives.

Seasonal Symbolism

Each sabbat also carries its own mood:

- Imbolc: renewal, cleansing, first stirrings of life.

- Beltane: fertility, fire, passion.

- Lughnasadh: work, reward, community.

- Samhain: death, ancestors, memory.

- And so on through the cycle.

The symbolism is flexible and you don’t need to believe in gods to use it. The festivals are reminders of rhythm, balance, and return.

Photo by Stevan Gabriel: https://www.pexels.com/photo/woman-with-black-and-red-flower-tattoo-standing-behind-blue-flowers-813961/

How Practitioners Use It Today

So how is the Wheel used in practice? That depends on who you ask.

Some Wiccans mark each sabbat with formal ritual: circles cast, invocations made, candles lit. Others keep it simple - maybe a shared meal, a single candle, or a quiet walk outdoors. Some groups gather for public festivals, especially at Beltane or Samhain, which lend themselves to fire, costumes, and community celebration.

Timing varies. Some insist on the exact astronomical moment of solstice or equinox. Others shift to the nearest weekend. In urban life, it’s rarely practical to light a bonfire at midnight on a Tuesday. Flexibility keeps the Wheel alive.

Offerings are common - bread baked at Lughnasadh, apples left out at Samhain, herbs burned at Litha. These aren’t sacrifices in the old sense; they’re tokens of thanks, ways to mark the passing of time with intention.

Importantly, the Wheel isn’t exclusive to those living in rural landscapes. City witches adapt: a candle on the windowsill for Yule, flowers on a desk for Ostara, bread baked in a flat for Lughnasadh. The point isn’t scale, it’s actually rhythm. Even the smallest act keeps you in step with the turning.

The Wheel Beyond Wicca

Although Wicca popularised the Wheel, it isn’t confined there. Druids use it, often with different emphasis. Heathens sometimes adapt it to fit Norse festivals. Eclectic Pagans blend it with local customs. Even people outside any defined Pagan path use the Wheel as a mindfulness tool: a calendar of pause points in a life otherwise driven by work schedules and artificial holidays.

That’s part of its strength, because the Wheel is portable or adaptable. You can graft it onto different mythologies, or strip it down to bare seasonal markers. You don’t need to believe in gods at all - you just need to recognise that the seasons turn and that marking them gives life meaning.

Criticisms and Alternatives

Not everyone buys into the Wheel as it stands. There are three main criticisms worth noting.

1. It’s Modern, Not Ancient

Some Pagans bristle at the claim that the Wheel is ancient. They point out, correctly, that while the festivals have old roots, the eightfold structure is a modern invention. For them, authenticity is damaged by the reconstruction.

2. It Doesn’t Fit Every Climate

The eight sabbats make sense in Northern Europe, where they were forged. But in tropical or desert climates, they can feel irrelevant. A bioregional approach - creating wheels based on local seasons, like monsoon cycles or dry/rainy seasons - may be more meaningful.

3. It Can Become Rote

Some practitioners complain the Wheel becomes a checklist: light this candle, bake this bread, move on. If the symbolism is forgotten, the practice becomes hollow. Like any ritual, the Wheel only works if it’s engaged with consciously.

That said, criticisms don’t weaken the Wheel - they push it to adapt. The calendar has always been flexible. Its power isn’t in rigid rules but in the turning itself.

In Conclusion

So, what is the Wheel of the Year? It’s not a relic of ancient Europe. It’s not a perfect calendar for every climate. It’s not even the same for everyone who uses it. What it is is a living symbol: a circle of festivals, a rhythm of time, a reminder that endings and beginnings are the same thing seen from different angles.

The Wheel is useful precisely because it isn’t fixed. It can be myth, metaphor, ritual, or mindfulness tool. It can be solemn or joyful, collective or solitary, rooted in gods or stripped to symbols. It is, ultimately, a way of keeping time that feels human, natural, and real.

If you want to get into the weeds of each sabbat - their names, meanings, and how to celebrate them - read our other article on the Eight Sabbats of Wicca. But if all you take away from this is that time moves in circles, not straight lines, then you’ve got the heart of it. The Wheel turns. Always has. Always will!