What Does Satan Mean?

Share

Satan is one of the most recognised names in human history, but also one of the most misunderstood. Depending on who you ask, Satan is either a supernatural villain, a metaphor for human freedom, a literary character, or nothing at all. The word conjures everything from Biblical dread to heavy metal album covers to anti-authoritarian slogans.

The meaning of “Satan” shifts dramatically across different belief systems, time periods, and ideologies. For some, he’s the embodiment of evil. For others, he’s not even a person - just a symbol of opposition or doubt. And then there are those who see Satan not as a force to fear, but as a figure to admire.

This article breaks down what Satan actually means, in religion, in culture, literature, and philosophy. By stripping away myth and hysteria, we can get a clearer picture of what this name has come to represent - and why it still provokes such strong reactions.

Key Points:

- Satan has evolved from a biblical accuser to a symbol of rebellion, individualism, and cultural resistance.

- His meaning changes depending on context - religious, literary, philosophical, or political.

- Modern Satan is often used metaphorically, not as a literal being, but as a tool to challenge norms and authority.

- Understanding what Satan represents helps reveal deeper fears, values, and power structures in society.

By Gustave Doré - Invaluable.com, Public Domain, Link

The Biblical Origins

The name “Satan” comes from the Hebrew word śāṭān, which simply means “accuser,” “adversary,” or “opponent.” In the earliest Biblical texts, Satan isn’t a proper name. It’s a job title, describing someone who challenges or obstructs, like a kind of celestial prosecutor.

One of the first clear appearances is in the Book of Job. Here, Satan is a member of God’s divine council. He doesn’t rebel against God - he works for Him. His role is to test Job’s faith by taking away his wealth, health, and family. He acts with permission, not in opposition. There’s no mention of Hell, horns, or eternal damnation.

In other parts of the Old Testament, the word satan is used generically to describe human or angelic adversaries. For example, in 1 Samuel 29:4, David is referred to as a satan by Philistine commanders - simply meaning “opponent” in war. The term didn’t carry the sinister baggage it would later acquire.

Over time, especially in post-exilic Jewish texts and apocryphal writings, the figure of Satan began to shift. Influences from Persian dualism and other regional mythologies helped turn this once-neutral figure into a more malevolent one. But in early scripture, Satan was not an enemy of God - he was more like a cosmic tester of character.

So originally, Satan wasn’t the ruler of Hell or a symbol of evil. He was a sceptic, a challenger, and a necessary part of divine justice. That version would later be buried under layers of Christian theology, but it’s the starting point for everything that came after.

Evolution in Christian Theology

In Christian theology, Satan undergoes a major transformation. What began as a title meaning “accuser” turns into a full-blown character: the enemy of God, the tempter of mankind, and the ruler of hell. This version of Satan (the one most people picture today) is a later development, shaped by centuries of interpretation, myth-building, and fear.

The shift starts in the New Testament. Here, Satan appears as a personal being who tempts Jesus in the desert, opposes the apostles, and is described as the source of evil. By this point, he’s no longer a servant acting under God’s permission - he’s a rogue force. The idea of Satan as a rebellious angel starts to take shape, although the Bible never gives a detailed account of his supposed fall.

The connection between Satan and Lucifer is another layer of reinterpretation. The name “Lucifer” comes from a Latin translation of a verse in Isaiah, which was originally referring to a Babylonian king. Early Christian writers like Origen and Augustine later applied it to Satan, turning a poetic insult into a backstory; the angel who tried to rise above God and was cast down.

By the time the medieval Church took over, Satan had become a central figure in Christian thinking. He was blamed for temptation, illness, heresy, and just about everything else the Church wanted to warn people against. The devil grew horns, wings, a tail (none of which are found in the Bible) and became the tormentor-in-chief of an eternal hell.

This version of Satan was useful. It kept people afraid. It gave priests a clear enemy to preach against. And it helped explain suffering without blaming God. The devil became the scapegoat for human weakness, a figure that justified punishment and moral control.

So the Christian Satan isn’t a direct continuation of the Hebrew adversary. He’s something new - a theological invention that reflects the Church’s priorities, politics, and worldview. He’s not just an accuser anymore. He’s the embodiment of sin, pride, and disobedience, and a constant reminder of what happens when you challenge divine authority.

Satan in Islam and Other Traditions

In Islam, Satan appears in a different form - as Iblis, a being made from smokeless fire. He’s not an angel, but a jinn - a creature with free will. His story is similar to the Christian fall narrative, but with key differences. When God creates Adam, He commands the angels and jinn to bow. Iblis refuses, claiming he is superior because he was made from fire, while Adam was made from clay. For this arrogance, he is cast out.

Unlike the Christian devil, Iblis doesn’t rule hell. His punishment is delayed until the Day of Judgment, and until then, he is allowed to tempt humans. His goal is to lead people astray, but only with God’s permission. He cannot force anyone, he can only whisper and suggest. This is why he is often called Shaytan, which means “deceiver” or “tempter.”

Islam places responsibility for sin on the individual. While Iblis tempts, humans still choose. There’s no doctrine of original sin, and Satan doesn’t have ultimate power. He is a cautionary figure - arrogant, bitter, and full of pride - but he is not equal to God, and his fate is sealed.

Outside of the Abrahamic religions, the idea of an ultimate adversary varies widely. In some Eastern traditions, such as Hinduism or Buddhism, there is no direct equivalent to Satan. Evil is often seen as a result of ignorance or imbalance, not the work of a malicious being. That said, there are figures like Mara in Buddhism - a tempter who tries to prevent enlightenment - which echoes aspects of Satan as a distractor or disruptor.

In ancient mythologies, similar adversarial spirits appear; tricksters, destroyers, or chaotic forces. But none of them match the Western Satan in scope or symbolism. That version is unique to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam - and even between those, the details are wildly different.

What’s clear is that Satan, or his equivalent, reflects each culture’s values and fears. In Islam, he’s a test. In Christianity, he’s a fallen rebel. In Judaism, he’s a divine challenger. The name might be the same, but the meaning depends entirely on the system you’re in.

By Warner Bros. Records - Billboard, page 7, 18 July 1970, Public Domain, Link

Satan as a Cultural Symbol

Outside religion, Satan has taken on a life of his own as a symbol, an icon, and in some cases, a brand. Once Christian Europe had cemented Satan as the face of evil, artists, writers, and philosophers began to rework the character. What started as a warning turned into a figure of rebellion, intellect, and defiance.

In literature, Satan shifts dramatically. In John Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), he’s portrayed as a tragic antihero. Proud, eloquent, and driven, Milton’s Satan famously declares, “Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven.” While Milton didn’t mean to glorify the devil, many readers came away sympathising with him. That image - the rebel angel cast down for refusing submission, really stuck.

Romantic writers picked it up in the 18th and 19th centuries. Poets like Byron and Shelley embraced the Satanic figure as a stand-in for the misunderstood genius, the defier of tyrants. In this view, Satan isn’t evil - he’s the price of independence. He’s what happens when you refuse to kneel.

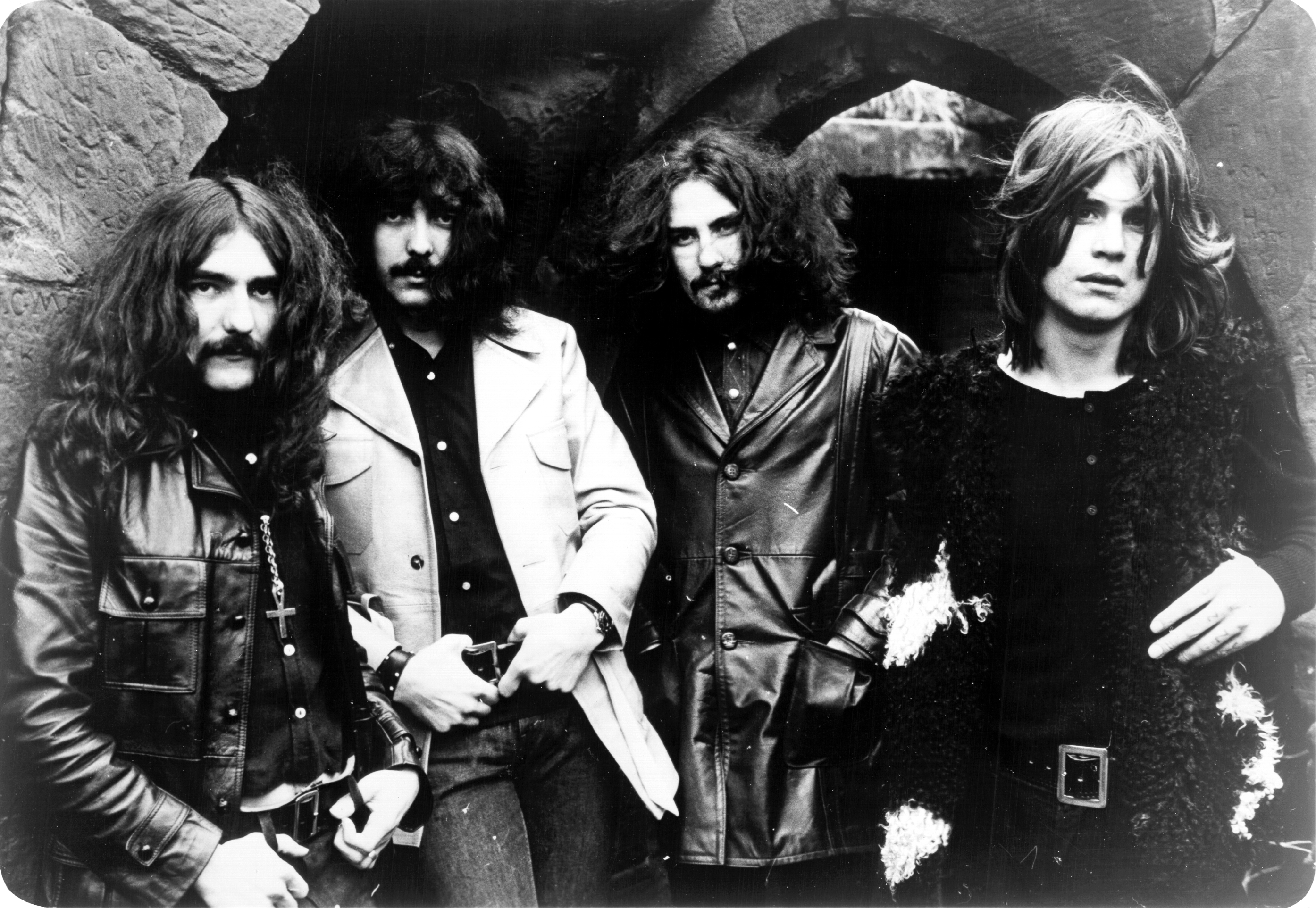

By the 20th century, Satan had become a fixture of pop culture. Horror films, comic books, and rock music all borrowed his imagery - sometimes for shock, sometimes for satire. Bands like Black Sabbath and Iron Maiden used Satanic symbols to provoke authority. Horror directors plastered films with pentagrams and demonic possessions. Even cartoons and TV shows joined in, turning Satan into everything from a scary villain to a comedy character.

At the same time, Satan was adopted by actual movements. In art, he became a metaphor for pushing boundaries. In politics, he was used to mock the religious right. For many in the counterculture, Satan stood for freedom from social norms. Not because they believed in him, but because they didn’t. He was the ultimate outsider.

This symbolic Satan became more useful than the religious one. He could represent rebellion, critical thinking, sexual liberation, nonconformity, or just plain resistance to authority. Whether admired or mocked, he never quite disappeared. He evolved - from evil spirit to literary character to cultural tool.

So even for people who don’t believe in the supernatural, Satan remains relevant. He’s not about fire and brimstone anymore. He’s about standing alone, speaking freely, and refusing to bow no matter the cost.

The Philosophical and Secular Satan

In the 20th century, Satan took another major turn - this time as a philosophical symbol, stripped of supernatural meaning. The most famous example came with the founding of the Church of Satan in 1966 by Anton LaVey. Here, Satan wasn’t a being at all. He was a metaphor. A deliberate rejection of religion, conformity, guilt, and blind obedience.

LaVeyan Satanism presents Satan as a symbol of pride, indulgence, rational self-interest, and personal strength. He’s the rebel who refuses to submit, the thinker who questions authority, the outsider who chooses his own path. LaVey’s The Satanic Bible outlines this worldview - blending atheism, individualism, and social commentary into one darkly theatrical package.

This secular Satan isn’t evil. He doesn’t tempt or deceive. He represents the parts of human nature that traditional religion tries to suppress: desire, confidence, anger, and ambition. Where Christianity might see those traits as sins, Satanism sees them as natural, even necessary.

Other groups followed. Some focused more on activism, like The Satanic Temple, which uses Satanic imagery to challenge religious privilege and promote secularism. Others remain philosophical and inward-looking. What they all share is a use of Satan as a rhetorical tool - a way to question dominant moral narratives.

Philosophers and writers have also played with the figure. Thinkers like Nietzsche didn’t endorse Satanism, but they respected the symbolism - especially when criticising Christianity’s emphasis on guilt and submission. Satan, in this context, became a kind of stand-in for free will, defiance, and moral complexity.

Importantly, most of these movements are non-theistic. They don’t believe in a literal Satan. They use him to explore ideas, to represent the freedom to think differently, live unapologetically, and reject imposed moral systems. For many, this makes Satan not a villain, but a mirror - showing who we are when no one else is watching.

So in modern secular thought, Satan means something very different from fire and punishment. He’s the critic. The challenger. The humanist in disguise. Whether serious or satirical, his image persists. Probably because every generation needs something to push against.

By Master L. Cz. (anonymous German Engraver) - Scan of PD artwork reproduced in book, Public Domain, Link

Is Satan Misunderstood?

Satan is one of the most misunderstood figures in religious and cultural history. Much of what people think they know about him has little to do with original texts or theology. It’s a mix of folklore, medieval fear, Hollywood exaggeration, and urban legend.

First, Satan is not the same figure across all religions. In early Judaism, he wasn’t evil - just a tester. In Christianity, he became the enemy of God. In Islam, he’s a jinn called Iblis, not a fallen angel. The roles vary massively depending on the belief system. Treating all versions as one character leads to confusion.

Another myth: Satan looks like a red demon with horns, goat legs, and a pitchfork. That image doesn’t come from the Bible. It was pieced together from pagan gods, medieval art, and Renaissance theatre. The goat imagery, for example, comes from the Greek god Pan and later associations with witchcraft. The horns and hooves were meant to scare peasants, not represent any specific doctrine.

People also tend to confuse Satanism with devil worship. Most self-described Satanists don’t believe in any supernatural being at all. Groups like the Church of Satan and The Satanic Temple are atheistic. They use Satan as a symbol, not as someone to worship. Real devil worship is rare, fringe, and often rooted in misunderstood or invented practices.

Then there’s the idea that Satan is responsible for all evil. That’s a theological stretch. In the Bible, he tempts and accuses - but the blame for sin falls on people. In Islam, Satan can suggest, but not force. The concept of Satan as a puppet master pulling every evil string is more of a later invention than a scriptural fact.

The last major misconception is that Satanists are criminals or dangerous. This belief exploded during the Satanic Panic of the 1980s, when false claims of ritual abuse swept the media. Decades of investigation found no evidence to support those stories. They were fuelled by bad therapy, poor journalism, and moral panic - not actual Satanic organisations.

In short, the image of Satan most people have in their heads is built on fiction. He’s not necessarily a monster, not always religious, and not inherently violent. Understanding what Satan really means - in each context - strips away the fear and reveals a much more complex symbol.

Why the Meaning Still Matters

Satan isn’t just an old religious figure that belongs to dusty scriptures or horror films. The idea of Satan - what he represents, how he’s used, and why people still talk about him, says a lot about how societies think about power, freedom, guilt, and control.

At its core, Satan has always been a mirror. In theology, he reflects moral failure. In culture, he reflects rebellion. In philosophy, he reflects independence. Whether he’s feared or admired, Satan is a figure that provokes questions: Who decides what’s right? What happens when you defy authority? What do we call someone who refuses to conform?

This is why the meaning still matters. For religious believers, Satan is a real threat - a symbol of temptation or a literal enemy. For secular thinkers, he’s an idea that helps expose contradictions in moral or political systems. And for artists, writers, and musicians, he’s a tool for expressing defiance, satire, or complexity.

In politics, the label “satanic” is still used to smear people, often with zero understanding of what it means. That kind of fear-based language is a sign that Satan still has power - not as a person, but as a concept. He becomes a placeholder for whatever society fears, hates, or doesn’t understand.

Even in modern Satanic groups, the symbol matters. It gives people a way to challenge norms, mock hypocrisy, or reclaim power. It forces others to confront their assumptions. You don’t have to agree with it, but you can’t deny it makes people uncomfortable, and sometimes that discomfort reveals more than any sermon.

So whether you believe in Satan, reject him, or use him as a metaphor, the meaning is never static. It evolves with culture. And each version, from the Biblical adversary to the literary antihero to the philosophical rebel, shows how much a single name can carry.